With international climate negotiations putting Indigenous Peoples and other local communities in the spotlight for climate funding, more attention is being paid to protecting those groups’ rights to their land and forest.

That often takes the form of land titling programs, but titles alone don’t guarantee rights. And while tenure security can make communities more secure, exactly what that means varies from place to place, according to a new study by the Center for International Forestry Research and World Agroforestry (CIFOR-ICRAF).

“I think a lot of people still believe that land titles grant tenure security, and it’s hard to get away from this idea,” said CIFOR-ICRAF principal scientist Anne Larson. “Data show that people often consider a piece of paper reassuring — a sign of legitimacy meaning that others will respect their rights. But anyone who has worked in this field for very long knows how limited a title can be.”

Larson has seen cases in which a newly titled community’s leader has sold off forest rights to the highest bidder, or an Indigenous community has won title only to have government agencies fail to support its efforts to defend itself against settlers who invade its land.

“It’s frustrating to share in the victory of seeing a title granted to an Indigenous community that has been fighting for it for so long, only to see all the apparent advantages of having that title practically eroded by the time it is delivered,” she said.

So what do communities expect from land tenure?

“In a study that included communities in Indonesia, Uganda and Peru, we found that many things matter for the well-being of Indigenous Peoples and local communities, but secure tenure is the foundation,” Larsen said. “The study shows how multiple factors that influence well-being are interconnected.”

If a title does not ensure tenure security, however, what does?

Visions of the future

When Larson and her colleagues dug into what forest dwellers mean by tenure security, they found that it varies from place to place but with important common threads.

They used a method called participatory prospective analysis, in which people involved in tenure issues — community members, government representatives, members of non-governmental organizations and academics — created future scenarios involving land and forests.

The result, Larson said, was a more comprehensive understanding of how tenure relates to the livelihoods, identity, and the overall well-being of local communities.

The three countries were chosen because they reflected various tenure models, from ownership of forest resources by Indigenous or traditional communities to arrangements in which communities and state entities share forest management.

Multiple workshops were held in the three countries in 2015 and 2016, leading the participants through a five-step process. In the first step, they defined their situation, answering questions such as: ‘What is the future of tenure security in this region 20 years from now?’

Once that was defined, they identified factors that could have a positive or negative impact on forest and land tenure. They then examined how those factors affected each other, to identify the most influential or ‘driving’ forces — the ones that could lead to a domino effect

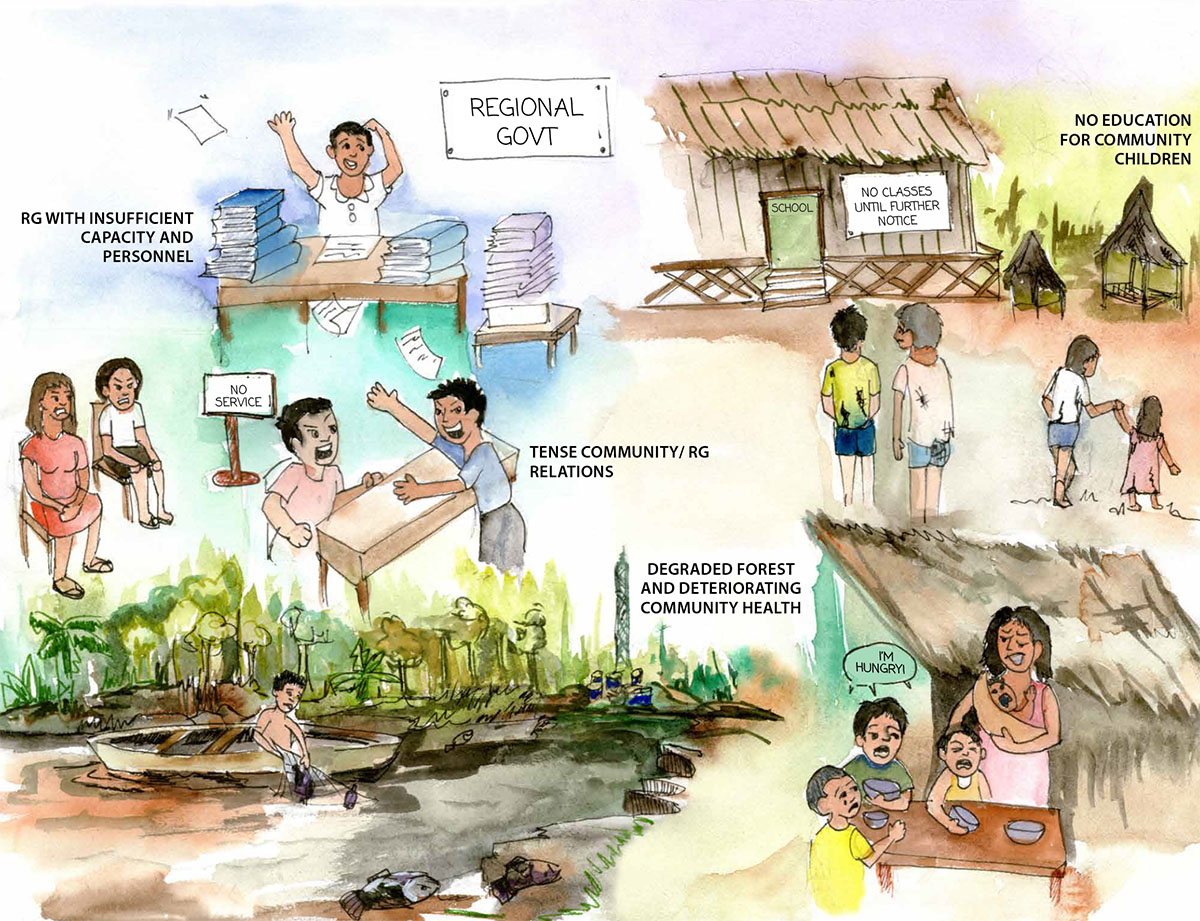

After determining what those drivers would look like if they were positive or negative, the participants chose the most logical combinations of factors to create a variety of different potential future scenarios. They built narratives around those, and in Peru, an artist produced drawings of each. The groups then created action plans to work toward their desired futures.

Examples of the drawing of an optimistic and pessimistic scenario from the Peru sites. Illustrations by Lesky Zamora Rios (watercolor on paper and digitized).

Context and history matter

Communities in the regions chosen for the study have different types of tenure and face various pressures from outside their territories, and the scenarios the workshop participants developed show that local characteristics and history are important.

In Peru’s Loreto and Madre de Dios regions, the government has been granting titles to Indigenous communities, but many communities still lack titles, and overlapping claims abound. Communities do not have rights to subsoil resources, such as oil and minerals, and can use forest resources but cannot own them.

In positive future scenarios, workshop participants stressed coordination between national and local governments and between the government and communities, a central role for Indigenous Peoples, transparency, effective monitoring, and governments with sufficient capacities and resources. Negative scenarios, which represented backsliding in rights, included elements such as a lack of government coordination, lack of interest in Indigenous issues and corruption.

In Indonesia’s biodiversity-rich Maluku region, much of the forest is managed by communities under a customary system, while in the Lampung province of Sumatra, the expansion of commercial plantations led to a tenure reform under which communities manage state forest areas. As in Peru, overlapping claims are a source of conflict in both places.

Positive visions of the future included consistent and transparent policies, government support for communities and respect for customary rights, and a greater role for women in managing forest resources. Negative scenarios included unclear policies, forest degradation, inadequate budgets, poor coordination, and lack of collaborative forest management.

In Uganda, workshops were held in three regions: Lamwo, where forests are managed through customary, clan-based institutions; Masindi, with a mix of private, government-managed, and communal forests; and Kibaale, where most forests are on private land.

Positive scenarios stressed the importance of collaboration between government and communities, trained government staff, adequate funding, available information, and highly participatory policy development. Negative visions of the future were characterized by corruption, lack of government support and funding, unclear policies, political favouritism, and lack of community participation in forest management. The published study includes a model of factors that influence security.

The scenarios clearly show that for forest dwellers, legal rights are only one aspect of tenure security, Larson said. Government officials and others must also listen to communities’ needs and help them bring their visions of the future to fruition, taking into account the different factors that make that possible in each place.

“Our research findings suggest that communities’ visions of a positive future depend on factors besides titles, especially community governance, the role of the state and the relationship between communities and the state,” she added. “A title will only bring security if other conditions are in place, and although those conditions have some general characteristics, such as organized communities, they also are specific to a place’s context and history.”

What does this mean for scholars and practitioners of community and Indigenous land rights? “It means deeper engagement with Indigenous Peoples and local communities,” she said, “as well as the importance of listening to peoples’ needs and visions for the future, supporting their self-determination to act on these and fostering the enabling conditions in each specific context.”

The Global Comparative Study on Forest Tenure Reform, carried out by the Center for International Forestry (CIFOR), was funded by the European Commission and the Global Environmental Facility (GEF), with technical support from the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

This study was part of the CGIAR Research Program on Policies, Institutions and Markets (PIM), led by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), and the CGIAR Research Program on Forest, Trees and Agroforestry (FTA), which was led by CIFOR.

We want you to share Forests News content, which is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). This means you are free to redistribute our material for non-commercial purposes. All we ask is that you give Forests News appropriate credit and link to the original Forests News content, indicate if changes were made, and distribute your contributions under the same Creative Commons license. You must notify Forests News if you repost, reprint or reuse our materials by contacting forestsnews@cifor-icraf.org.