We want you to share Forests News content, which is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). This means you are free to redistribute our material for non-commercial purposes. All we ask is that you give Forests News appropriate credit and link to the original Forests News content, indicate if changes were made, and distribute your contributions under the same Creative Commons license. You must notify Forests News if you repost, reprint or reuse our materials by contacting forestsnews@cifor-icraf.org.

Nining Liswanti is a researcher with CIFOR-ICRAF Indonesia. She has an undergraduate degree in forestry from the University of Gajah Mada and a master’s degree on Environment and Natural Resource Management from Bogor Agriculture Institute. She has worked on a wide range of research activities including biodiversity assessment, multidisciplinary landscape assessment, land use planning, forest and land tenure, Trees on Farms (TonF), multistakeholder processes, and gender and climate change, and is currently researching REDD+ safeguards for Indigenous Peoples and local communities in Indonesia. She has experience working with diverse stakeholders from local to national level across Indonesia’s forestry sector.

Q: Why did you become a scientist? What motivates you in your work?

A: I like working with nature and people, in particular local communities in and around the forest (including women and ethnic minority groups); I like traveling; I like to have new opportunities and experiences. And I could get all of this when I started working at CIFOR, by doing different kind of research activities, both biophysical and social science, on different islands across Indonesia. In addition, Indonesia’s tropical forests consist of high biodiversity richness, as well as diversity in culture and indigenous ethnic groups. This has become my motivation: to learn something new and – if we can – to contribute to direct and indirect benefits for local communities in this country.

Q: Can you share an example of a barrier you overcame to become a scientist? What about an opportunity (situation or person) that pulled you forward in your career?

A: Currently I think that women and men have the same opportunities and challenges in science. I have been lucky to work with great scientists at CIFOR who gave me opportunities to improve my knowledge and skills with their support. If we want to try and learn to do something new, doors to careers will open. However, working in remote forest areas can be quite challenging for women, who often cannot be as free as men when doing activities with communities. They may also be quite dependent on men – especially in villages with no electricity or facilities, as walking alone during the night wasn’t an easy thing for a woman. Sometimes, if my son or daughter got sick while I was in the field, as a mother I felt worried because I was far away from home.

Q: What does it mean to you to be a woman in science?

A: I am proud to be a woman who contributes to science, because this proves that women can progress if we want to. At CIFOR-ICRAF for example, there is a significant number of women in science. I have worked with several women researchers who demonstrate patience, thoroughness, creativity and innovation – as well as the persistence needed to complete the work.

Q: Why is it important to have women leading in science?

A: In Indonesia nowadays there are many leading women who occupy top positions, both in government and non-governmental sectors. This is because when women become leaders it is very beneficial for the organisation, as they can see from sides that are not visible. In addition, the number of women in Indonesia who are seizing opportunities to work in science is increasing over time. This phenomenon is now quite common across Indonesia, and I think it will have a positive impact. Happy International Women’s Day!

______

Read more about Nining Liswanti’s work:

Trust-building in a multistakeholder forum in Jambi, Indonesia

Tenure reform and perceived food security in Indonesia: An exploratory study

Falling back on forests: how forest-dwelling people cope with catastrophe in a changing landscape

______

This is the fourth in a series of Q&As with women scientists at the Center for International Forestry Research and World Agroforestry (CIFOR-ICRAF). Ahead of the International Day of Women and Girls in Science (11 February), we asked them what motivates them, any barriers they overcame, what it means to them to be a woman in science, and why it’s important for women to have equitable positions and adequate representation in the sector. Read the Q&As with bioenergy scientist Mary Njenga, food and nutrition scientist Mulia Nurhasan, and post-doctorate research fellow Eponle Usoh Sylvie.

For more information on Nining Liswanti’s work, please contact her at N.Liswanti@cifor-icraf.org

For more information about CIFOR-ICRAF’s work on gender equality and social inclusion (GESI), please contact Elisabeth Leigh Perkins Garner (e.garner@cifor-icraf.org) or Anne Larson (a.larson@cifor-icraf.org).

We want you to share Forests News content, which is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). This means you are free to redistribute our material for non-commercial purposes. All we ask is that you give Forests News appropriate credit and link to the original Forests News content, indicate if changes were made, and distribute your contributions under the same Creative Commons license. You must notify Forests News if you repost, reprint or reuse our materials by contacting forestsnews@cifor-icraf.org.

“In the hushed pre-dawn darkness, the first sounds of daylight begin to filter through the forest understory. As the trees take shape against faint light in the eastern sky, a troop of Guianan red howler monkeys awakens with a mighty roar, their voices fading in and out on the soft breeze. A marail guan, the namesake marudi of these hills, launches from a high perch with a few loud flaps, displaying to a female hidden in the canopy below. As the last of the night’s frogs retire to their daytime haunts, a chorus of birds – woodcreepers, forest-falcons, toucans and antpittas – swells amid the shadows. The first sunlight reaches the highest canopy crowns, where flowers begin to swarm with an army of insects eager for nectar. Daylight advances, and the forest comes alive.”

The Marail Guan can be found in abundance in the Karaawaimin Taawa area. ©FAO/Marlondag

The compelling paragraph above describes the experience of international bird scientist, Brian O’Shea, waking up in the camp in Karaawaimin Taawa, a remote mountain range in the rainforests of Rupununi in southern Guyana. It appears in an upcoming book on a community-led bio-cultural assessment, which was carried out via a three-week-long expedition involving local and international wildlife experts, in March 2022.

The region is one of the biodiverse ecosystems in the world, but prior to this body of work, there was no comprehensive assessment of the flora and fauna therein. It’s traditional territory of the Wapichan Indigenous people; presently, though, their rights to the land are not legally recognized. That’s important, because gold mining is being considered in the Karaawaimin Taawa area, threatening water systems, biodiversity, and community livelihoods.

“Community members fear that they will not be able to drink the water and eat the fish because of mercury contamination, which has already happened in some places due to mining,” said Andrew Snyder, who is the Key Biodiversity Area Coordinator at Re:Wild, and one of the eight international researchers who joined the expedition.

In that context, leading Indigenous organization South Rupununi District Council (SRDC) has been taking steps to ensure that their homeland’s natural treasures are seen and valued. With support from the Sustainable Wildlife Management (SWM) Programme, a major international initiative which aims at improving wildlife conservation and food security, SRDC started the organization of a biodiversity expedition to the area. SWM’s role was key in developing a collaborative network between community experts and scientists and ensuring that local knowledge was integrated in all phases of the expedition. “The idea was to go in and collect as much baseline biodiversity data to supplement the knowledge that the locals already have about this area to make a very thorough comprehensive case for why this area should not be opened up for gold mining,” said Snyder.

“What we’re hoping is that we have enough strong data, and enough of an international media push, to ensure that local indigenous communities can continue to benefit from this resources and be responsible for protecting their own land,” he said.

Local experts working alongside international scientists to gather extensive data of the taxa of dung beetles in the Karaawaimin Taawa area. ©FAO/Marlondag

Little-charted territory

For the international researchers, the expedition was exciting and fruitful – if at times difficult given accessibility challenges, bad weather, and abundance of mud. “This is a very remote and wild area,” said Brian O’Shea, a collections manager in ornithology at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences in the United States; “and any time you go somewhere where there aren’t many people, you tend to find a lot of wildlife.” O’Shea was part of the team focusing on birdlife, which also included a local bird expert, Asaph Wilson (see our Q+A with him here). “We found high diversity, and a very much intact bird community,” he said. Many of the species the team found were “very common, and not at risk now – but mining would inevitably lead to tragedy in short consequence,” he said.

Snyder, for his part, focused on getting a snapshot of the amphibian and reptile species in the area. “Basically, I would go out every single morning for several hours, and every single night for four, five, six hours, to do general opportunistic surveys,” he said. “I would target as many different habitats that were around our campsite as possible – swamps, rivers, forests away from the creek, adjacent to the creeks. When all’s said and done, we should be able to make estimates of the total number of species that live within the area, and of how many species we didn’t find that might occur there, based on the number of different species. So, I will be making estimates of abundance for particular species, as well as a general diversity number.”

International scientist Andrew Snyder holds up a smooth-fronted caiman caught during the assessment. ©FAO/Marlondag

At lower elevation areas, the team encountered amphibians and reptiles that could be considered relatively widespread – although as Snyder noted, “at least with amphibians, what we’re finding these days is that what were once considered widespread species actually consist of multiple species masquerading under one name…. So several of what I encountered on this trip, I know full well within the next few years are going to be considered smaller species.”

In the extremely isolated upland areas, the scientists found – as expected – higher levels of endemism. There, they encountered a high number of yellow-footed tortoises [Chelonoidis denticulatus], which are listed as vulnerable on the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species.

They also recorded a species of snake that had not yet been recorded for Guyana, and several species of frogs which “may well be entirely new species to science; or they may be species that have been recorded in other countries and Brazil, and just have not yet been recorded here,” said Snyder; “genetic analysis is required to tease that out.”

This Short-nosed Leaf Litter Snake is a new discovery to Guyana. ©Andrew Snyder

While such analysis remains to be done, Snyder – who has traveled extensively across Guyana over the past 11 years and surveyed a lot of different locations – said that “in just a few short days on this trip, it was immediately apparent that this location is incredibly biodiverse. It was something that that you noticed on the ground, rather than having to go back and look at your data afterwards.”

Aside from the taxonomic findings, the scientists spoke highly of the process itself, and the opportunity to exchange knowledge with local experts on the trip. “We don’t often get the opportunity to truly collaborate,” said O’Shea. “Here, we felt like we were transferring useful skills amongst ourselves– we all showed a real desire to learn from each other.” The local experts were essential to the success of the assessment, given their experience in the terrain, their knowledge of local species and their sensorial capacities were essential whilst scientists contributed with standard methods and tools for recording observations and data.

The reptiles and amphibian team, like the other taxa’s, consists of local experts and international scientist. ©FAO/Marlondag

It was also apparent that the assessment ought to be seen as just one step in building up a comprehensive picture of biodiversity in the area. “The very last day, we recorded three new species that we hadn’t recorded during the previous days,” said Snyder; “I can only imagine how many more species occur there that we just didn’t have the time, or we weren’t in the right place at the right time, to see – so much is chance when you’re doing these types of surveys. But it really did strike me that it was an incredibly biodiverse place, and it would be heart-wrenching to see anything happen to it.”

This is the third article in a three-part series on the Karaawaimin Taawa Biodiversity Assessment, the results of which will be published in April 2023. Read the other two articles here and here.

_____

The SWM Programme in Guyana is part of an initiative from the Organisation of African, Caribbean and Pacific States (OACPS), funded by the European Union with co-funding from the French Facility for Global Environment (FFEM) and the French Development Agency (AFD). It is being implemented by a dynamic consortium of partners that includes the CIFOR, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the Wildlife Conservation Society, and the French Agricultural Research Centre for International Development (CIRAD). Its aim is to improve food security and the conservation and sustainable use of wildlife in forest, savannah, and wetland environments in 15 countries.

For more information about the SWM Programme in Guayana, contact Nathalie van Vliet at nathalievanvliet@yahoo.com.

We want you to share Forests News content, which is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). This means you are free to redistribute our material for non-commercial purposes. All we ask is that you give Forests News appropriate credit and link to the original Forests News content, indicate if changes were made, and distribute your contributions under the same Creative Commons license. You must notify Forests News if you repost, reprint or reuse our materials by contacting forestsnews@cifor-icraf.org.

The forests of Central Africa, which include the Congo Basin – a carbon sink like no other, absorbing more carbon than forests of the Amazon and South-East Asia – are at risk of climate change, environmental degradation, deforestation and population explosion. And the countries of the sub-region have a problem. They lack the requisite financial resources to preserve the ecosystem widely known as the ‘lungs of Africa’ which holds at least 80 billion tons of carbon.

Despite the essential role forests of Central Africa play in sequestering global carbon emissions, a new report produced by the Central Africa Forest Observatory (OFAC) has shown that forests of the sub-region do not seem to attract much funding like their counterparts of Amazon and South-East Asia. Between 2008 and 2017, the forests of Central Africa managed to secure only about 11% of international financial flows destined to sustainable management and conservation of the world’s tropical forests, according to the report titled Congo Basin Forests – State of the Forests 2021.

So far, funds mobilized for the forests of Central Africa partially pass through the executive secretariat of the Central Africa Forests Commission (COMIFAC); a body created in 1999 to coordinate conservation and ecosystem management efforts as well as the fight against climate change in Central Africa. COMIFAC has a convergence plan, supplemented by a business roadmap, which serves as blueprint.

The report indicates that member states of the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) instituted a self-financing mechanism known as Community Integration Contribution (CCI); a 0.4% tax levied on products imported from countries outside ECCAS and consumed by member states. To finance its own operations and activities, 0.1% of the CCI is supposed to be automatically retroceded to COMIFAC. But ECCAS has faced difficulties recovering the CCI tax and the quota destined to COMIFAC has not been paid continuously, according to the researchers. The CCI however remains an important income stream for COMIFAC, with 320 million francs CFA pumped in by ECCAS in 2018.

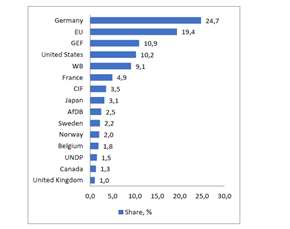

Share of Forestry and Environmental Official Development Assistance. Source: Favada et al. 2019

Another source of income highlighted in the report is member states’ annual contribution which stands at 45 million francs CFA per country. Though designated as a primary source of income, member countries have not been contributing regularly. Besides Cameroon which has been paying its dues in full, the arrears stood at 3 billion francs CFA in 2021.

“This laxity in own contributions do not permit COMIFAC to fully assume its missions. The fact that no sanctions exist for countries which fail contribute and no advantage for those that are up-to-date doesn’t permit COMIFAC to shine,” Richard Eba’a Atyi, Regional Coordinator of CIFOR-ICRAF Central Africa Office, a contributor to the chapter of the report, said.

The report also shows that international partners and development actors have been very instrumental in setting up programs, projects and platforms to support COMIFAC’s Convergence Plan. Notable amongst the interventions is Germany’s 147-million-euro commitment made between 2005 and 2022 in favour of Central Africa’s forests. The European Union also mobilized 14 million euros between 2007 and 2022 to support OFAC operations. In addition, the EU has been a key donor to the Central African Forest Ecosystem (ECOFAC) program, the last of its six phases which required 85.5 million euros.

Signing ceremony on 26 July 2012 in Rome of a regional forestry project between FAO and the Central Africa Forests Commission (COMIFAC) to help Congo Basin countries set up advanced national forest monitoring systems. Photo by Alessia Pierdomenico/FAO

Between 2008 and 2017, bilateral and multilateral financial flows to towards the forest and environmental sectors in Central Africa amounting to US$ 2 billion have been irregular, and have since 2015 been on the decline, according to the report. Environmental Official Development Assistance represented more than three quarters of total Forestry and Environmental Official Development Assistance. While Germany, EU, Global Environment Facility, United States and the World Bank, in descending order, were the five top donors, DR Congo, Chad, Cameroon, Rwanda, and Gabon, in descending order, were the five major beneficiaries.

Based on the study, the five major themes covered in Central African forests by international aid include biodiversity, environmental policy and administrative management, forestry policy and administrative management, environmental research and the protection of the biosphere. These five themes gulped 89% of all Forestry and Environmental Official Development Assistance, which, according to the researchers, represents an imbalance in attribution and is detrimental to the sub-region. Forestry administration and environmental education/training accounted for the lowest share – less than 0.03% each – while environmental research, forestry education and training, wood energy, and forestry research received negligible funding.

Citing a study commissioned in 2021 by COMIFAC to elaborate its Convergence Plan, the researchers indicate that about US$ 191.3 million would be required to execute priority actions between 2021 and 2025 in Central Africa. The researchers suggest that COMIFAC could raise this money from several sources, amongst them: African Development Bank, European Union, UNFCCC funds administered by World Bank and UN, Germany, Norway, United Kingdom initiative, as well as international non-governmental organisations.

To achieved this, the researchers recommend that COMIFAC should up its game, strengthening communication and its participation in international debates in order to draw the attention of international actors to the importance of the forests of Central Africa.

We want you to share Forests News content, which is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). This means you are free to redistribute our material for non-commercial purposes. All we ask is that you give Forests News appropriate credit and link to the original Forests News content, indicate if changes were made, and distribute your contributions under the same Creative Commons license. You must notify Forests News if you repost, reprint or reuse our materials by contacting forestsnews@cifor-icraf.org.

This blog presents preliminary findings of our research on REDD+ safeguards in Indonesia’s East Kalimantan province. The results were validated with key REDD+ stakeholders in East Kalimantan in June 2022.

Early criticism of the potential impact of REDD+ (the UNFCCC’s mechanism to reduce deforestation and forest degradation) on Indigenous Peoples (IPs) and local communities (LCs) has led to the development of a suite of ‘social safeguards’. These have been designed and conceptualized in various ways, and range from serving as barriers against potentially harmful impacts (‘do no harm’) to mechanisms that could catalyse improved well-being and livelihoods for IPs and LCs and their territories (‘do better’).

Under the Center for International Forestry Research – World Agroforestry (CIFOR-ICRAF)’s Global Comparative Study on REDD+ (GCS-REDD+), we are researching the design and implementation of REDD+ safeguards in Indonesia, Peru, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). At the national level, we reviewed legal documents and interviewed specialists to understand the state of the recognition and protection of the rights of customary groups and local communities in the context of REDD+.

At the sub-national level, we are combining our deep engagement with REDD+ in Indonesia with an exhaustive literature review and interviews with actors with experience with safeguards – including NGOs, government actors, and university-based researchers – as well as representative groups affected by them. This study includes the national Safeguard Information System (SIS) and the World Bank’s Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF) initiative in East Kalimantan.

Our goal is to understand how safeguards (refers to the Cancun safeguards on IPs and LCs rights and its participation on REDD+) have been implemented, examine barriers to their implementation, and provide lessons to address those barriers.

Safeguards in East Kalimantan

East Kalimantan is one of Indonesia’s most experienced provinces in terms of REDD+ safeguards. Indonesia started its official ‘interpretation process’ of the Cancun Safeguards by developing its SIS in 2011. SIS REDD+ is an important tool to document the FCPF’s safeguards implementation. There has been close coordination between the provincial government and the national government on SIS REDD+, specifically on technical aspects related to safeguard reporting. However, the FCPF safeguard standard requires strict compliance over aspects related to IPs and LCs rights, and this will need to go beyond what is required from SIS REDD+, as it results from the articulation of the Cancun safeguards. A year later, the first national safeguard was created, namely the PRISAI (Prinsip, Kriteria, Indicator Safeguard REDD+ Indonesia); both SIS and PRISAI were initially disseminated and trialled in East Kalimantan. In parallel, East Kalimantan developed its own social and environmental standards for REDD+ in 2012, with criteria and indicators that responded to the provincial context.

More recently, activities in East Kalimantan under the FCPF were compelled to align with the World Bank’s safeguarding guidelines to be eligible to receive results-based payments. East Kalimantan is committed to reducing CO2 equivalent emissions by 22 metric tons by 2024, for results-based payments totalling USD110 million – of which USD20.9 million has already been received by the Government of Indonesia.

Local NGOs, in coordination with the Project Management Unit (PMU), played a crucial role in supporting safeguard implementation in the province, and furthering East Kalimantan’s compliance with the World Bank’s safeguards requirements.

For instance, our research found that free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) workshops were carried out in 99 out of 150 targeted villages in early 2022. We also found that an integrated feedback grievance and emission reduction performance benefits mechanism system has been established, and reports from existing grievance and performance benefits portals from land-based government agencies will also be monitored.

A benefit sharing mechanism has also been developed: importantly, it ensures that both recognized and unrecognized communities access benefits from REDD+. East Kalimantan has a legal base in place for recognition of adat communities. Through a provincial regulation 1/2015, adat communities’ legal rights are recognized and protected, further becoming a legal precedent for customary communities to pursue their legal customary forest rights. There are also various schemes that are formulated under social forestry policy to provide customary and local communities legal rights to the forest. Unlike customary forests, which give the ownership rights to the recipients, others are contract-based schemes of 35 years, with possible extension in the future. This is a positive development, as unrecognized adat communities – those that have yet to receive legal recognition for their customary identity and forest territories – tend to be excluded from these initiatives. Under the mechanism, the intermediary bodies, selected by the Indonesian Environment Fund (BPDLH) of the Ministry of Finance, distribute benefits and/or incentives from the FCPF to the village government and community groups, including recognized adat groups. Mr Pathur Rachman As’ad, the chief of the PMU mentioned that “the adat community group who do not yet legally recognized would be also received benefits of the emission reduction of FCPF’s program through their village government”.

From ideas to implementation

Despite laudable progress on safeguarding in some arenas and landscapes, we also found that knowledge on their design and implementation was not uniform. This was particularly apparent when we presented our early analysis of the review and interviews in a workshop with REDD+ stakeholders in Samarinda, East Kalimantan’s capital, on June 16th 2022. During discussions, participants held different perceptions of how the safeguards’ design and implementation processes had played out: in their interventions, some referred to reports while others referred to on-the-ground implementation. Only those who had engaged directly – for instance, who had participated in the organization of FPIC processes or in the preparation of safeguards documents – were able to understand and explain the process. This suggests that a clearer strategy could support the communication process for clearer transparency and understanding of safeguards.

In general, while prior discussions had emphasized the existing systems and formal documents produced to date, it was found that reflection on the implementation of those systems and plans had not yet taken place. Ali Suhardiman, a scientist at the University of Mulawarman, reminded attendees that “[Our] focus should now shift toward how to move forward, from ideas and systems to real innovation on the ground.” Further, the national-level respondent added to the importance of capacity building for implementers to understand policy and gaps of safeguards implementation between sectors. It was also noted that mainstreaming gender in the FCPF program is also important; from here, the GCS-REDD+ project will further analyse how gender is mainstreamed in safeguards implementation.

From beneficiaries to partners

According to Juan Pablo Sarmiento, a CIFOR-ICRAF scientist, the research project as a whole “aims to understand how REDD+ safeguards can support a rights-based transformation and generate more equitable engagements with forest-based communities as rights-holders and partners – and how such an approach can be implemented.”

The experience in East Kalimantan – where unrecognized communities are included in the benefit sharing mechanism for REDD+ – reveals the potential impact that standards may have, given that rights aspects in safeguards are partially aligned with Indonesia laws and public policy. Further analysis from East Kalimantan will allow us to synthesize lessons to support a rights-based REDD+.

This research is part of CIFOR-ICRAF’s Global Comparative Study on REDD+. The funding partners that have supported this research include the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad, Grant No. QZA-21/0124), International Climate Initiative (IKI) of the German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, and Nuclear Safety (BMU, Grant No. 20_III_108), and the CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry (CRPFTA) with financial support from the CGIAR Fund Donors.

We want you to share Forests News content, which is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). This means you are free to redistribute our material for non-commercial purposes. All we ask is that you give Forests News appropriate credit and link to the original Forests News content, indicate if changes were made, and distribute your contributions under the same Creative Commons license. You must notify Forests News if you repost, reprint or reuse our materials by contacting forestsnews@cifor-icraf.org.

As a food and nutrition scientist in CIFOR-ICRAF, Mulia Nurhasan leads the execution of the food and nutrition component of environmental projects, mostly in Indonesia. Her team comprises four nutritionists, geospatial analysts, and a livelihood specialist. She also leads collaboration between CIFOR-ICRAF and partner institutions, supporting the implementation of research projects in the field. Mulia has a bachelor degree in post-harvest fishery, a master’s degree in international fisheries management, and has a PhD from the University of Copenhagen, Department of Human Nutrition. She is actively involved in advocating for a sustainable food systems agenda in Indonesia.

Q: What does your work look like on a daily basis?

A: My work involves leading the design of projects, building research protocol, liaising with partners institutions, managing research and researchers in the field, managing data analysis, leading the interpretation of findings, leading the process of research publication and writing proposals for research funding.

Q: Why did you become a scientist? What motivates you in your work?

A: I began my career working in development. I knew it was the kind of work I wanted to do from the beginning – I love going to the field, meeting communities, getting to know people with various backgrounds, and contributing to development processes. I am also curious about things, question the mainstream, and love to investigate, write, and share what I find. So being a researcher in development fits my character. But I didn’t know that one could be a researcher in development: I thought researchers belonged to academia, and development was another world. Towards the end of my PhD, things unfolded for me. I met my current mentor, Amy Ickowitz – a senior scientist at CIFOR-ICRAF – with whom I decided to work continuously for sustainable food systems through science and development.

Why is it important to have women leading in science? Do you have a specific example or story you can share?

A: I grew up in an environment that warns women to behave and conform to the general norms. For most of my life, when I speak up against or for something, I am often made to feel bad for doing so. Consequently, like many Asian women who grew up like me, we choose a leadership style that is low key and persuasive. This has been a good approach, but it also has consequences. Sometimes people don’t see women as leaders, doubt our capacity to lead and manage, and hesitate to give us big responsibilities. In many cultures, leading is dominating, leaders must show masculine characteristics.

I feel very fortunate that throughout my career, especially at CIFOR-ICRAF, I have met with great women in science who have many different styles coming from various backgrounds, and they are great scientists, great leaders too! They make me realize that we women do not have to hide our true colours, character and femininity. We can still be great leaders by being who we are and who we are meant to be.

Women of different characters who have taken on leadership roles are playing a vital role in educating our society to accept and provide equal opportunities for women to lead. Their courage to stay true to their characters and bring new types of leadership styles not only inspires more women to embrace their authentic selves but also empowers them to pursue leadership positions. It is not always easy for women to step up to leadership roles. Many of us are not nurtured or shaped for it. But it is unthinkable to design, conduct, and write research without or with very few women in your science group, when half of the target population in research and development work is women. Therefore, women leading in science is a prerequisite to success in our work.

It is not always easy for women to step up to leadership roles. Many of us are not nurtured or shaped for it. But it is unthinkable to design, conduct, and write research without or with very few women in your science group, when half of the target population in research and development work is women. Therefore, women leading in science is a prerequisite to success in our work.

Mulia Nurhasan, CIFOR-ICRAF scientist

This is the second in a series of Q&As with women scientists at the Center for International Forestry Research and World Agroforestry (CIFOR-ICRAF). Ahead of the International Day of Women and Girls in Science (11 February), we asked them what motivates them, any barriers they overcame, what it means to them to be a woman in science, and why it’s important for women to have equitable positions and adequate representation in the sector. Read the first Q&A with bioenergy scientist Mary Njenga.

Read more about Mulia Nurhasan’s work:

- Healthier mangroves, more fish

- Toward a Sustainable Food System in West Papua, Indonesia: Exploring the Links Between Dietary Transition, Food Security, and Forests

- Changing forests, changing diets in Papua

- Food consumption patterns and changes in Indonesia forested and deforested areas

- Caretakers’ perceptions and willingness‐to‐pay for complementary food in urban and rural Cambodia

- Linking food, nutrition and the environment in Indonesia

For more information on Mulia Nurhasan’s work, please contact her at M.Nurhasan@cifor-icraf.org

For more information about CIFOR-ICRAF’s work on gender equality and social inclusion (GESI), please contact Elisabeth Leigh Perkins Garner (e.garner@cifor-icraf.org) or Anne Larson (a.larson@cifor-icraf.org).

We want you to share Forests News content, which is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). This means you are free to redistribute our material for non-commercial purposes. All we ask is that you give Forests News appropriate credit and link to the original Forests News content, indicate if changes were made, and distribute your contributions under the same Creative Commons license. You must notify Forests News if you repost, reprint or reuse our materials by contacting forestsnews@cifor-icraf.org.

Over a decade from the adoption of seven safeguard principles for REDD+ by the United Nations 2010 Climate Change Conference (UNFCCC COP16), the national implementation of two safeguards that address Indigenous Peoples and local communities (IPs and LCs) remains a work in progress.

Researchers examining the implementation of the safeguards in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) – considered a ‘fast mover’ on REDD+ – found that national laws which were meant to align with these safeguards are still far from addressing the envisioned inclusivity. The Cancun safeguards mandate that countries interpret these principles themselves, deferring to national law in deciding – for example – what counts as ‘respect’ or ‘participation’ for IPs and LCs.

The research, which was part of CIFOR-ICRAF’s Global Comparative Study on REDD+, found that despite the existence international conventions that recognize the rights of Indigenous Peoples, the DRC until recently had no national law providing the relevant legal content and protection mechanisms.

The study was carried out by University of Kisangani law professor Marie-Bernard Dhedya Lonu, together with CIFOR-ICRAF social anthropologist Juan Pablo Sarmiento Barletti and governance, equity and well-being Team Leader Anne Larson. They found that some of the laws in the DRC still challenge the equitable inclusion of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in REDD+ and the benefits that will be derived from it.

“For example, collective ownership of land acquired in accordance with law or custom is guaranteed by the provisions of Article 34 of the Constitution,” the researchers wrote. “But land ownership in the DRC is exclusively vested in the state and, in practice, communities and individuals can only hold rights of enjoyment, use, usufruct, passage and concessions on state land.”

The authors also found that respect accorded to the constitutionally recognized collective ownership rights to land poses serious problems in practice because, in accordance with articles 387, 388, and 389 of the Land Law, they must be detailed by a presidential ordinance, which has not been issued to date.

However, the research revealed that DRC has made progress in resource rights for local communities since the 2002 Forestry Code, including through Decree No. 14/018 (August 2, 2014), which allows communities to obtain forest concessions with perpetual and imprescriptible titles. “Local communities can also obtain conservation concessions whereby the government entrusts them (totally or partially) with the use and management of forest and wildlife resources for the conservation of biological diversity,” wrote the researchers. “However, implementing community forestry and biodiversity conservation concessions is challenging due to the procedural costs involved and the technical skills required.”

Furthermore, a 2018 Ministerial Order on REDD+ affirmed that forest carbon stocks are the property of the state, but recognized that units of emissions reduction are owned by those who invest in REDD+, including communities. DRC has also ratified relevant treaties and conventions, leading to the adoption of general standards for the promotion and protection of women’s rights.

Another significant step forward in terms of inclusion is the 2022 law on the promotion and protection of the rights of Indigenous Pygmy Peoples. “In addition to providing a definition of Indigenous Peoples (“Hunter-gatherer peoples generally living in the forest,” distinguished “by their cultural identify, their way of life, their attachment and closeness to nature and their endogenous knowledge”), this law proposes a normative framework for the protection of Indigenous Peoples in the DRC, said the researchers.

DRC is also currently revising its Land Law, and its revisions are expected to give more consideration to local communities and secure their rights through the establishment of customary land registries and other mechanisms.

CIFOR-ICRAF’s Global Comparative Study on REDD+ is funded by the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad), the International Climate Initiative (IKI) of the German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU), the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry (CRP-FTA).

We want you to share Forests News content, which is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). This means you are free to redistribute our material for non-commercial purposes. All we ask is that you give Forests News appropriate credit and link to the original Forests News content, indicate if changes were made, and distribute your contributions under the same Creative Commons license. You must notify Forests News if you repost, reprint or reuse our materials by contacting forestsnews@cifor-icraf.org.

Peru has recognized the role of Indigenous Amazonian Peoples for ensuring the sustainable use of one the world’s most biodiverse biomes and realising its climate and conservation plans. However, community forest management, or CFM, has struggled to deliver on its promise of environmental and livelihood improvements. In Peru, as in many other tropical forest countries, communities are often unable to comply with forestry regulations and are pushed to the informal sector, where unjust commercial relations and unsustainable practices predominate.

There have been numerous efforts to promote CFM, but a lack of coordination and continuity among programs has thwarted progress. National policymakers, NGO technicians, Indigenous-rights activists, and donors also have diverse views on what CFM means and their roles in supporting it.

“Stakeholders generally agree that community forest management is a good idea, but it often gets bogged down by clashing views on how it should be implemented in practice,” said Peruvian social anthropologist Juan Pablo Sarmiento Barletti. “Understanding the various perspectives and identifying points of agreement is crucial to creating a CFM that works for both peoples and forests.”

A new Center for International Forestry Research and World Agroforestry (CIFOR-ICRAF) study led by Sarmiento Barletti used a systematic process known as Q-Methodology to identify different viewpoints across actors, bringing to light the areas of dissent and – most crucially – consensus. The work seeks to provide them with a solid foundation for developing and implementing more effective CFM strategies.

Beyond focus groups

Q-Methodology blends statistical analysis and qualitative interviews to cut through the participants’ unconscious biases and clarify the range of perspectives on a specific topic. Building on previous applications of the approach in Peru, the research team worked with a sample of indigenous leaders, policymakers, NGO technicians, university professors, final year forestry students, and representatives of donor organisations.

The scientists started by identifying five hypothetical approaches to community forest management in specialised literature and producing a set of 40 statements reflecting the various perspectives. They then had participants rate the statements based on how strongly they agreed or disagreed with each of them. Finally, the actors were interviewed to understand the reasoning behind their sorting. An ensuing statistical analysis revealed the existence of four main perspectives on CFM.

CIFOR-ICRAF senior scientist and co-author Peter Cronkleton noted the importance of using such a systematic process: “In a group discussion on a multi-faceted topic, individuals might believe that others share their definitions and points of reference and may not be conscious of how their understandings of that topic differ,” he said. “The approach we used helps put these individual perceptions into words and makes it possible to compare them and identify similarities or differences.” Q-Methodology also leads people to reflect on things they might not have thought about otherwise and forces them to distil their priorities.

Shared priorities

The process revealed participants’ perceptions on CFM fell into four categories – it should either: balance conservation with support for community rights; encourage capacity and enterprise development; be a technical approach to protect forests in the territories of Indigenous Peoples; or be primarily geared towards supporting grassroots Indigenous autonomy.

The same analysis identified points of consensus across those groups. For example, they agreed that CFM should place equal emphasis on community rights and conservation goals and that profits should not be a principal indicator of success.

They also agreed that Indigenous Peoples needed support to build their capacities—especially, to stop logging companies from walking away with most of the profits, while leaving them with the legal and environmental impacts of timber extraction.

“The areas of consensus could provide a point of departure for developing strategies to address the challenges driving informal logging and unjust extractive relationships,” said the study. “This would necessarily re-target the role of government in supporting Indigenous Peoples to develop dignified and sustainable livelihoods from their forests through capacity development and a supportive regulatory framework.”

The shared priorities identified by the research could act as an early agenda for collaboration among the actors promoting CFM in Peru, and provide a basis for regulatory reform, noted the researchers.

Different viewpoints

The study identifies common ground, as well as pinpointing key differences in opinion between groups that also need acknowledging – for example on the role of the government as a referee in commercial transactions and in the granting of industrial extractive permits in areas managed by communities.

Other points of disagreement include the importance of technical plans and community rights, the promotion of communal enterprises, the legitimacy of existing norms and sanctions, and the use of heavy machinery.

While some perspectives saw community forestry as a technical pursuit, others placed more emphasis on the environmental management and stewardship practices of Indigenous Peoples. Similarly, there is a tension between balancing support for their right to self-determination with the need for environmental law enforcement and governmental oversight of timber sales.

“The government needs to be aware that there is little consensus on these matters, which might exacerbate conflicts in the future,” pointed out the authors, who urged dialogue on these topics to prevent disputes down the line and create more equitable policies.

Q-methodology can facilitate dialogue in community forestry and in other initiatives with a wide array of stakeholders, opinions, and goals, the researchers said. Wherever there is a cacophony of perspectives, it can put analytical order in how people perceive the issues at stake and bring shared priorities to the fore, helping pull complex discussions out of the rut and onto the policy road.

This study was undertaken as part of the CGIAR Research Program on Policies, Institutions and Markets (PIM), led by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). It was also funded by the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD).

For more information on this topic, please contact Juan Pablo Sarmiento at J.Sarmiento@cifor-icraf.org or Peter Cronkleton at P.Cronkleton@cifor-icraf.org

We want you to share Forests News content, which is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). This means you are free to redistribute our material for non-commercial purposes. All we ask is that you give Forests News appropriate credit and link to the original Forests News content, indicate if changes were made, and distribute your contributions under the same Creative Commons license. You must notify Forests News if you repost, reprint or reuse our materials by contacting forestsnews@cifor-icraf.org.

While women have made immense advances in scientific fields in recent years, the numbers still don’t tell an equitable story. Across the world, they’re typically given smaller research grants than their male colleagues, and researchers tend to have shorter, less well-paid careers; their work is underrepresented in high-profile journals and they are often passed over for promotion. They represent about a third of all researchers – and only 12% of members of national science academies.

This is the first in a series of Q&As with women scientists at the Center for International Forestry Research and World Agroforestry (CIFOR-ICRAF). Ahead of the International Day of Women and Girls in Science (11 February), we asked them what motivates them, any barriers they overcame, what it means to them to be a woman in science, and why it’s important for women to have equitable positions and adequate representation in the sector.

Nairobi-based Mary Njenga is a research scientist at CIFOR-ICRAF and a visiting lecturer at Wangari Maathai Institute for Peace and Environmental Studies at the University of Nairobi. She did a Postdoctorate in bioenergy at ICRAF and holds a PhD in Management of Agroecosystems and Environment, an MSc in Biology of Conservation, and a BSc in Natural Resource Management.

Centred on Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 7: Affordable Clean Energy, while also integrating SDG 5: Gender Equality, Njenga’s research focuses on sustainable and efficient biomass energy production and use systems and their interconnections with environment including climate change, livelihoods, circular bioeconomy, and rural-urban linkages. She also works on adaptive technology development and transfer, including gender integration and co-learning through transdisciplinary approaches. She is passionate about communicating research findings and lessons and has published over 190 publications, and contributed to raising over USD7 Million for research she believes in. She aims to contribute to improving energy and food security, health, eliminating poverty, promoting gender equality, enhancing sustainable ecosystems services, rural and urban development, and mitigating climate change.

Q: Why did you become a scientist? What motivates you in your work?

A: My motivation as a woman scientist is to create the change I want to see. Growing up in rural Kenya, I experienced first-hand the difficulties of meeting basic human needs. I watched my mother and older sisters being denied opportunities to be who they wanted to be. I made a decision to be an instrument of change to improve livelihoods and the environment we depend on – even if it took incremental improvements on a one-brick-at-a-time basis.

When I discussed this with my father, he said: “Mary, if you want to make decisions to improve your life and that of other girls and women, you need to be academically and financially empowered.” Our journey together began at an early age, in primary school, and it was transformative. He supported my career path – beginning with my education. He mentored me, and most importantly he shifted perceptions and rules in our household and extended family on girls’ responsibilities, and protected me against social-cultural norms that saw my ambitions as an unbecoming expectation for a girl. Thank heavens my mother and oldest sister played along and overcame the societal peer pressure that came their way for allowing me to grow up the way I wanted to.

Q: Can you share an example of a barrier you overcame to become a scientist? What about an opportunity (situation or person) that pulled you forward in your career?

A: Barriers and hurdles date back to childhood. Having adequate time for homework and revision was a challenge due to competing domestic chores like cooking meals after school. I negotiated to be allowed to fetch a few cans of water from the river, which took less time [than cooking]. Nevertheless, I still had to stay up late studying under a tin lamp.

When I completed primary school, I knew I needed much more time for studying – especially the sciences I was interested in – and I asked my dad to take me to a boarding school. Kambaa Girls High School was a stone’s throw away from home, and he paid for me to be a boarder. I was one of only four pupils out of 75 who went on to university, where my career as a scientist began for real.

For many years, I have had women role models and mentors – including powerful and influential ones like Vickie Wilde of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, founder of AWARD Nancy Karanja of the University of Nairobi, Ramni Jamnadass of CIFOR-ICRAF, Yvonne Pinto of ALINe, and Ruth Mendum of Penn State University, and Wenda Bauchspies of the National Science Foundation. The list is endless. Having a supportive supervisor in Catherine Muthuri is also critical. Hanging out with Esther Njuguna-Mungai of ILRI, Wanjira Mathai of WRI, and Margaret Waruiru of Safaricom is a blessing. These are women with whom I open my heart, learn and enjoy friendship.

There are so many women role models for girls in Africa, and these kinds of networks are essential: if girls can’t find them by themselves, please can someone create the bridges?

Q: What does it mean to you to be a woman in science?

A: Being a woman in science is the most beautiful and fulfilling thing. I do the kind of work I love: engaging in a transformative agenda that touches on energy, emancipation, ecology, and the local economy. When I have to work harder than necessary “just because I am a woman’” (a phrase from Dolly Parton’s music), I do it with passion, though sometimes I feel disappointed “just because I am human”: that is when it really counts to have someone trustworthy to talk to.

Q: Why is it important to have women leading in science?

A: Each of us represents a collection of identities and perspectives. I am a woman, but I am also a Kenyan, a natural scientist, a person of faith, a member of my home village community, and a participant in the international dialogue about science and the advancement of human flourishing. When I initiate a project, I bring all of my identities and influences with me, and I look for a diversity of team members who do the same. No one has all the answers by themselves.

When I initiate a project, I bring all of my identities and influences with me, and I look for a diversity of team members who do the same. No one has all the answers by themselves.

Mary Njenga, CIFOR-ICRAF scientist

Let me give you an example. Domestic, repetitive, unpaid work – like carrying heavy loads of firewood from forests – and its associated drudgery on women and girls may look like an ordinary chore of accessing cooking energy, but I tell you it’s not. When women and girls narrate their likes and dislikes of firewood collection from forests to me as a scientist, the fact that I have lived this problem myself means I know there are better ways to bring firewood closer to home and use it in more efficient ways that blend with cooking culture. I wrote about this, with a research team that I led, in a 2021 publication.

It doesn’t matter who you are: please, be an instrument of change in transforming women and girls’ wellbeing. Make it one of your purposes in life. Watch this short film Purpose, which will walk you through my career pathway and hopefully be an inspiration in following your star.

At the end of the day, my generation of women scientists are trailblazers. We have proven that we can do the work, and that our complicated understandings of reality and the role of science are what the world requires if we are to solve multi-dimensional problems like climate change and global inequality.

Read more about Mary Njenga’s work:

- Transforming Kenya’s invasive ‘mathenge’ bushes into charcoal farms

- Recovering bioenergy in Sub-Saharan Africa: Gender dimensions, lessons and challenges

- Biochar for climate-change mitigation and restoration of degraded lands

- Charcoal production from invasive Prosopis juliflora in Baringo County, Kenya

- Science into policy: Participatory development of biomass energy regulatory instruments in Kenya

For more information on Mary Njenga’s work, please contact her at M.Njenga@cifor-icraf.org

For more information about CIFOR-ICRAF’s work on gender equality and social inclusion (GESI), please contact Elisabeth Leigh Perkins Garner (e.garner@cifor-icraf.org) or Anne Larson (a.larson@cifor-icraf.org).

We want you to share Forests News content, which is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). This means you are free to redistribute our material for non-commercial purposes. All we ask is that you give Forests News appropriate credit and link to the original Forests News content, indicate if changes were made, and distribute your contributions under the same Creative Commons license. You must notify Forests News if you repost, reprint or reuse our materials by contacting forestsnews@cifor-icraf.org.

Indonesia has the third-largest area of biodiversity-rich tropical forests in the world. The archipelago is considered one of the world’s 17 ‘megadiverse’ countries and houses two of the 25 global biodiversity ‘hotspots’. In 2015, however, the country experienced its worst forest fire disaster in almost two decades. In September and October that year, carbon emissions released by the fires reached 11.3 million tons per day – higher than the emissions of the entire European Union, which released 8.9 million tons daily over the same period.

In response to the disaster – and as part of wider efforts to restore 14 million hectares of degraded land, including two million hectares of peatlands – the Korean and Indonesian governments have developed a peatland restoration project which focuses on the ‘3Rs’: rewetting, revegetation, and revitalization. Activities include rewetting infrastructure, revegetating over 200 hectares with tree planting, and land revitalization in 10 villages surrounding the project site, as well as the creation of a small peatland education centre.

“We believe that this peatland restoration project will help create a sustainable ecosystem and have a productive impact on the community,” said Junkyu Cho, Korean Co-Director of the Korea-Indonesia Forest Cooperation Center (KIFC), during a symposium to share knowledge and experience gained from peatland restoration initiatives in several locations across Indonesia, on 7 December 2022 at CIFOR’s Bogor campus. The international symposium also aimed to enhance the network of researchers involved in peatland restoration and governance.

The research team, which hails from Korea’s National Institute of Forest Science (NIFoS) and the Center for International Forestry Research and World Agroforestry (CIFOR-ICRAF), will develop a model for restoring peatlands and other degraded lands in Indonesia in ways that make the most of science and technology and improve local livelihoods.

“We hope that various issues, such as climate change adaptation, nature-based solutions, and bioeconomy will be explored under the rubric of peatlands,” said Hyungsoon Choi, the director of NIFoS’ Global Forestry Research Division. The researchers are also helping to develop sustainable community-based reforestation and enterprises, said CIFOR-ICRAF Senior Scientist Himlal Baral.

During the symposium, Baral also shared information on CIFOR-ICRAF’s long-term Sustainable Community-based Reforestation and Enterprises (SCORE) project, which runs for the same period as the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration and provides valuable opportunities for research. The study involves identifying areas for restoration, and for planting sustainable timber and non-timber forest products. “We start with small demonstration trials, and we hope to scale up and achieve long-term impacts,” he said, adding that smart agroforestry is one of the options for restoration.

Nisa Novita, from local NGO Yayasan Konservasi Alam Nusantara (YKAN), shared some of her research into the mitigation potential of natural climate solutions for Indonesia. Her team found that the country offers a dramatic opportunity to contribute to tackling climate change by increasing carbon sequestration and storage through the protection, improved management, and restoration of drylands, peatlands, and mangrove ecosystems. “Protecting, managing, and restoring Indonesia’s wetlands is key to achieving the country’s emissions reduction target by 2030,” she said.

Several presenters shared models for cost-effective restoration. A-Ram Yang of NIFoS’ Global Forestry Division discussed a visit to the Perigi peatland landscape in South Sumatra in September 2022. Meanwhile, a team from Korea’s Kookmin University shared their experience assessing ecosystem services in North Korea’s forests with a view to adapting these for use in Indonesia.

Budi Leksono, a senior researcher at the Research Center for Plant Conservation and the Forestry, National Research, and Innovation Agency (BRIN), spoke of the potential of genetic improvement to serve restoration goals. “The use of improved seeds for plantation forests has been proven to increase the productivity and quality of forest products,” he said. “In accordance with the goal of restoration in Indonesia to restore trees and forests to degraded forest landscapes on a large scale, it should also be applied to the landscape restoration program to increase the added value of the land, and will have an impact on increasing ecological resilience and productivity.”

On a similar note, in a research collaboration with CIFOR-ICRAF, scientists at Sriwijaya University (UNSRI) developed a model for landscape restoration to be applied to wide range of species of high economic value, including Jelutung (Dyera costulata), Belangeran (Shorea balangeran), Nyamplung (Calophyllum inophyllum) and Malapari (Pongamia pinnata). One of the scientists, Agus Suwignyo, said that “the use of improved seeds for landscape restoration will have an impact on people’s welfare if this is also followed by implementing a planting pattern that is in accordance with the conditions of the land and the needs of the local community.”

Participating farmers also chose their own preferred species, such as jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus), avocado (Persea americana), mango (Mangifera indica), nangkadak (a hybrid of Artocarpus heterophillus and Artocarpus integer), sapodilla (Manilkara zapota), oranges (Citrus sp.), soursop (Annona muricata), rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum) and betel or areca palm (Areca catechu). From 2018 to 2020, UNSRI helped local farmers to develop smart agrosilvofishery, improved rice cultivation, introduce other economical rice crops, plant trees, and cultivate various local fish species.

The method showed positive results. “During the long dry season in 2018, the surrounding area was burned by other farmers, but our demo plot area was not burned,” said Suwignyo. “This year, we scaled up the area to 10 hectares.” The story echoed a common theme within the symposium: the importance of well-planned, multidisciplinary, evidence-based restoration that puts both people and nature first.

This research was supported by the National Institute of Forest Science, Republic of Korea and collaborated with National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), Republic of Indonesia ; Tropical Rainforest Reforestation Center of Mulawarman University; University of Muhammadiyah Palangkaraya; Center of Excellence for Peatland Research at Sriwijaya University.

We want you to share Forests News content, which is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). This means you are free to redistribute our material for non-commercial purposes. All we ask is that you give Forests News appropriate credit and link to the original Forests News content, indicate if changes were made, and distribute your contributions under the same Creative Commons license. You must notify Forests News if you repost, reprint or reuse our materials by contacting forestsnews@cifor-icraf.org.

With international climate negotiations putting Indigenous Peoples and other local communities in the spotlight for climate funding, more attention is being paid to protecting those groups’ rights to their land and forest.

That often takes the form of land titling programs, but titles alone don’t guarantee rights. And while tenure security can make communities more secure, exactly what that means varies from place to place, according to a new study by the Center for International Forestry Research and World Agroforestry (CIFOR-ICRAF).

“I think a lot of people still believe that land titles grant tenure security, and it’s hard to get away from this idea,” said CIFOR-ICRAF principal scientist Anne Larson. “Data show that people often consider a piece of paper reassuring — a sign of legitimacy meaning that others will respect their rights. But anyone who has worked in this field for very long knows how limited a title can be.”

Larson has seen cases in which a newly titled community’s leader has sold off forest rights to the highest bidder, or an Indigenous community has won title only to have government agencies fail to support its efforts to defend itself against settlers who invade its land.

“It’s frustrating to share in the victory of seeing a title granted to an Indigenous community that has been fighting for it for so long, only to see all the apparent advantages of having that title practically eroded by the time it is delivered,” she said.

So what do communities expect from land tenure?

“In a study that included communities in Indonesia, Uganda and Peru, we found that many things matter for the well-being of Indigenous Peoples and local communities, but secure tenure is the foundation,” Larsen said. “The study shows how multiple factors that influence well-being are interconnected.”

If a title does not ensure tenure security, however, what does?

Visions of the future

When Larson and her colleagues dug into what forest dwellers mean by tenure security, they found that it varies from place to place but with important common threads.

They used a method called participatory prospective analysis, in which people involved in tenure issues — community members, government representatives, members of non-governmental organizations and academics — created future scenarios involving land and forests.

The result, Larson said, was a more comprehensive understanding of how tenure relates to the livelihoods, identity, and the overall well-being of local communities.

The three countries were chosen because they reflected various tenure models, from ownership of forest resources by Indigenous or traditional communities to arrangements in which communities and state entities share forest management.

Multiple workshops were held in the three countries in 2015 and 2016, leading the participants through a five-step process. In the first step, they defined their situation, answering questions such as: ‘What is the future of tenure security in this region 20 years from now?’

Once that was defined, they identified factors that could have a positive or negative impact on forest and land tenure. They then examined how those factors affected each other, to identify the most influential or ‘driving’ forces — the ones that could lead to a domino effect

After determining what those drivers would look like if they were positive or negative, the participants chose the most logical combinations of factors to create a variety of different potential future scenarios. They built narratives around those, and in Peru, an artist produced drawings of each. The groups then created action plans to work toward their desired futures.

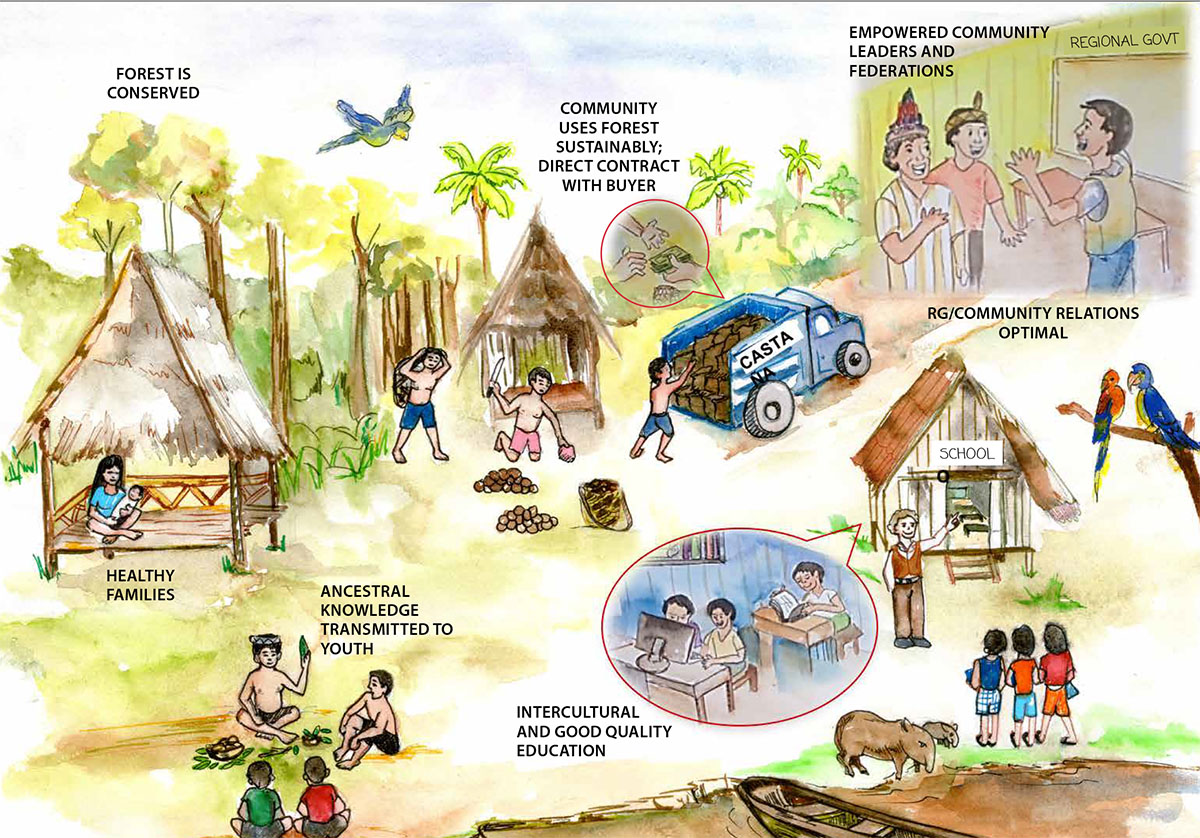

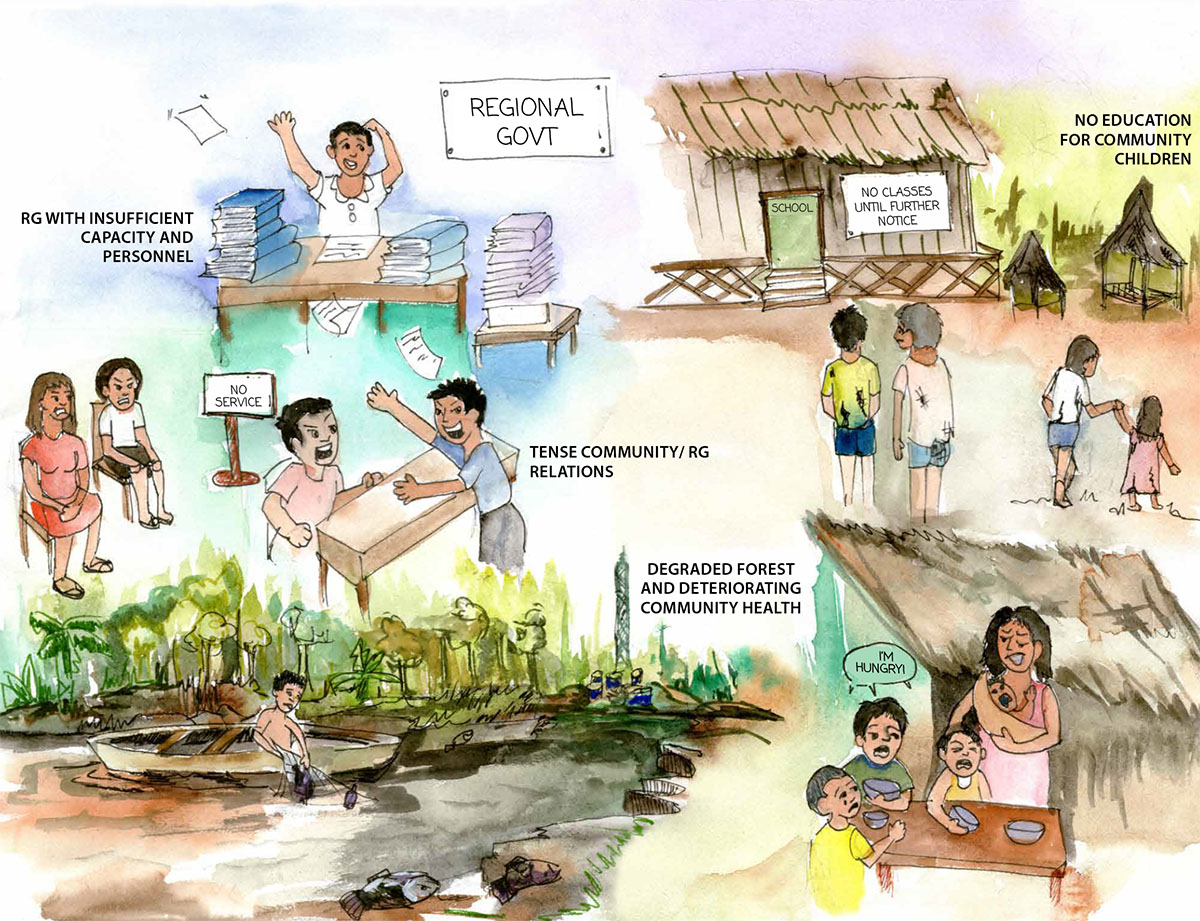

Examples of the drawing of an optimistic and pessimistic scenario from the Peru sites. Illustrations by Lesky Zamora Rios (watercolor on paper and digitized).

Context and history matter

Communities in the regions chosen for the study have different types of tenure and face various pressures from outside their territories, and the scenarios the workshop participants developed show that local characteristics and history are important.

In Peru’s Loreto and Madre de Dios regions, the government has been granting titles to Indigenous communities, but many communities still lack titles, and overlapping claims abound. Communities do not have rights to subsoil resources, such as oil and minerals, and can use forest resources but cannot own them.

In positive future scenarios, workshop participants stressed coordination between national and local governments and between the government and communities, a central role for Indigenous Peoples, transparency, effective monitoring, and governments with sufficient capacities and resources. Negative scenarios, which represented backsliding in rights, included elements such as a lack of government coordination, lack of interest in Indigenous issues and corruption.

In Indonesia’s biodiversity-rich Maluku region, much of the forest is managed by communities under a customary system, while in the Lampung province of Sumatra, the expansion of commercial plantations led to a tenure reform under which communities manage state forest areas. As in Peru, overlapping claims are a source of conflict in both places.

Positive visions of the future included consistent and transparent policies, government support for communities and respect for customary rights, and a greater role for women in managing forest resources. Negative scenarios included unclear policies, forest degradation, inadequate budgets, poor coordination, and lack of collaborative forest management.

In Uganda, workshops were held in three regions: Lamwo, where forests are managed through customary, clan-based institutions; Masindi, with a mix of private, government-managed, and communal forests; and Kibaale, where most forests are on private land.

Positive scenarios stressed the importance of collaboration between government and communities, trained government staff, adequate funding, available information, and highly participatory policy development. Negative visions of the future were characterized by corruption, lack of government support and funding, unclear policies, political favouritism, and lack of community participation in forest management. The published study includes a model of factors that influence security.

The scenarios clearly show that for forest dwellers, legal rights are only one aspect of tenure security, Larson said. Government officials and others must also listen to communities’ needs and help them bring their visions of the future to fruition, taking into account the different factors that make that possible in each place.

“Our research findings suggest that communities’ visions of a positive future depend on factors besides titles, especially community governance, the role of the state and the relationship between communities and the state,” she added. “A title will only bring security if other conditions are in place, and although those conditions have some general characteristics, such as organized communities, they also are specific to a place’s context and history.”

What does this mean for scholars and practitioners of community and Indigenous land rights? “It means deeper engagement with Indigenous Peoples and local communities,” she said, “as well as the importance of listening to peoples’ needs and visions for the future, supporting their self-determination to act on these and fostering the enabling conditions in each specific context.”

The Global Comparative Study on Forest Tenure Reform, carried out by the Center for International Forestry (CIFOR), was funded by the European Commission and the Global Environmental Facility (GEF), with technical support from the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

This study was part of the CGIAR Research Program on Policies, Institutions and Markets (PIM), led by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), and the CGIAR Research Program on Forest, Trees and Agroforestry (FTA), which was led by CIFOR.

We want you to share Forests News content, which is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). This means you are free to redistribute our material for non-commercial purposes. All we ask is that you give Forests News appropriate credit and link to the original Forests News content, indicate if changes were made, and distribute your contributions under the same Creative Commons license. You must notify Forests News if you repost, reprint or reuse our materials by contacting forestsnews@cifor-icraf.org.

Zambia’s agroecological miracle workers:

It has long been obvious that a truly regenerative agricultural system is one that minimises its dependence on external inputs like inorganic fertilisers, phytosanitary products and diesel.

Regenerative farmers focus on understanding, applying and exploiting the resources provided by every farm’s local ecology.

The study of natural ecosystems reveals that plants and animals never operate in isolation. Thriving ecosystems always include a multiplicity of producers, degraders and consumers, feeding off and nourishing each other in a never-ending dance whose only external inputs are rain, sunlight and the resources bacteria and fungi liberate from the soil’s underlying bedrock.

But making it work in real life can be a challenge for many farmers.

They have to worry not only about the functioning of their agroecosystems but also about feeding their families, meeting market demands, the unreliability of weather and dealing with their neighbours: in short, they must nurture their livelihoods above all else.

And they must do so in cognitive environments filled with conflicting information.

For most farmers, access to agricultural knowledge is mediated by actors that have ulterior agendas. Agricultural supply stores are not only wonderful places to meet other farmers and discuss the challenges of the day but are businesses that make their living from convincing as many farmers as possible to buy as much of as many inputs as possible. Agricultural advisors often support that agenda: the agricultural courses they took at university typically focussed on input-intensive mechanised agriculture and were often subsidised by the agricultural-input industry.

Despite these headwinds, the world is sprinkled with extraordinary farmers achieving amazing results by applying agroecological principles.

They combine the growing of annual crops and perennials such as trees and livestock in ways that deliver higher productivity, better resilience and much lower negative externalities.

It was to see one of the world’s most masterful such farmers that I recently visited Zambia.

Sebastian Scott, the son of Zambia’s vice-president Guy Scott, has devoted his career to the development of extraordinarily productive smallholding farming systems that require no inputs beyond sunlight, rain and the labour of human muscles and animal feet and snouts.

His playground is his farm near Kafue, where over years of combining crops, legumes, trees and livestock he is achieving levels of productivity that are so extraordinarily high that most commercial farmers simply cannot believe his figures.

In the most recent cropping season, he achieved maize yields of 16 tonnes per hectare, despite the presence of fall armyworm, a feared pest devastating maize across southern Africa. This easily surpasses the returns of the most intensive large farms in the American Midwest or in Brazil’s Cerrado and is a full order of magnitude more than most Zambian smallholders typically achieve with the help of subsidised fertiliser.

Scott achieves these results, which are being monitored by scientists from the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (known by its Spanish acronym CIMMYT: Centro Internacional de Mejoramiento de Maíz y Trigo), with intricate multi- and cover-cropping, the integration of several tree species, and the management, using mobile fences, of chickens and pigs as weed and pest controllers and legged fertiliser factories. He does not use machinery, inorganic fertilisers or pesticides. Every tool he uses is commonly available to Zambian smallholders and the farm always pays for its own investments.

“It is astonishing how quickly the farming system begins to deliver once you intercrop cereals with legumes, practice crop rotations, and integrate trees and animals,” he said.

But there are pitfalls: “If you don’t pay attention to your carbon–nitrogen ratios, even the best cow manure can go to waste”.

Getting it right may take practice but the first step is easy: “Make sure you have enough green matter in your mulch”.