We want you to share Forests News content, which is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). This means you are free to redistribute our material for non-commercial purposes. All we ask is that you give Forests News appropriate credit and link to the original Forests News content, indicate if changes were made, and distribute your contributions under the same Creative Commons license. You must notify Forests News if you repost, reprint or reuse our materials by contacting forestsnews@cifor-icraf.org.

Sink, shift, or sprout?

Timbulsloko Village seems to be sinking. At high tide, the ocean enters people’s houses, and licks at their floors and furniture. During storm surges and heavy rains, the sea takes bigger bites out of homes and pathways. The road through town, carefully paved with concrete, is sodden and impassable.

To adapt to the rising seas, people have rebuilt their houses on poles, and created meter-high walkways on stilts so they can move around without needing to wade or swim. They wheel their motorbikes to higher ground at the edge of town, and park their boats beside their homes instead.

This settlement in Demak Regency – on the northern coastline of Central Java in Indonesia – used to be a rice-growing area, well-known for its fertile river-delta soils. A wide green belt of mangroves protected the village from the waves and tides, as well as providing a reliable food source and habitat for fish and other marine animals. But in recent decades, lured by quick profits, villagers felled the trees along the shoreline and converted their rice fields to fishponds, where they began to farm prawns and milkfish [Chanidae chanos].

Since then, the village has been hard hit by erosion and flooding, and now sits below sea level. According to local fishers, catches have also decreased significantly as the mangrove habitat has disappeared, compromising livelihoods.

In response, some residents have cut their losses and gone to live elsewhere.

But others hold onto hope that by restoring the mangroves, they can save Timbulsloko.

Out at sea, they have made barricades of interconnected concrete blocks, which create temporary protection for mangrove seedlings until they are strong enough to stand against the waves and currents on their own. They have also created hybrid systems by making permeable structures out of natural materials. Sediment-laden seawater flows through the structures, which weaken the current; when the water flows back out, some of the sediment is deposited, gradually building up a bank behind the structure that protects against further assaults.

A multidisciplinary research team from the Center for International Forestry Research-World Agroforestry (CIFOR-ICRAF), Diponegoro University and Blue Forest Foundation hopes to help with this quest in Demak through the Restoring Coastal Landscape for Adaptation Integrated Mitigation (ReCLAIM) Project, which promotes evidence-based mangrove restoration for improved livelihoods, food security, and nutrition benefits for coastal communities. The project is a collaborative effort between CIFOR-ICRAF and several Indonesian partners representing universities, government agencies and civil society, with support from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation.

Alongside the work in Demak (which was chosen to represent mangroves that are being restored), ReClaim is being implemented in two other sites along the same coastline: one in Serang Municipality and Regency in Banten, which represents protected mangroves; and another in Banyuwangi Regency in East Java, which represents healthy mangroves.

Mangrove ecosystems are rather unique in terms of the socio-ecological systems they provide,” said CIFOR-ICRAF scientist Rupesh Bhomia. “Addressing climate change is important; addressing adaptation is important; but also, community health and nutrition are very important, and many projects fail to recognise or appreciate that third piece of the puzzle.”

In Timbulsloko, the researchers are assessing the rate of surface level change, and trying to ascertain its cause. “Possibly, this is happening due to the rising sea level, but another possibility is land subsidence,” said CIFOR-ICRAF Principal Scientist Daniel Murdiyarso in a video about the work in the village. “Which one is true? We want to measure it, to determine which of these things is happening.” To do so, they’re monitoring changes in soil sediment using the rod surface elevation table (RSET) technique, whereby a rod is driven into sediment to track whether soil is accumulating or eroding over time.

Through this method, they’re also tracking below-ground carbon storage – and they are monitoring above-ground storage by measuring tree diameters, too. Mangrove restoration in sites like this have the happy attribute of helping communities adapt to climate-change issues like sea-level rise and more extreme weather events, while mitigating the advance of climate change in the process.

Addressing climate change is important; addressing adaptation is important; but also, community health and nutrition are very important, and many projects fail to recognise or appreciate that third piece of the puzzle

“In general, if mangroves are thriving, they are able to trap the sediment and break up the wave energy, so typically the soils keep on increasing – and we get good carbon storage in the process,” said Bhomia. Globally, mangroves host around 1.6 percent of tropical forests’ biomass while occupying only 0.6 percent of their area, and they can put away four times the amount of carbon as tropical rainforests. Restoring and conserving the world’s mangroves could protect 18 million people from coastal flooding, and boost the productivity of the planet’s fisheries.

To that end, the researchers are also studying the effects of mangrove presence on community health and nutrition, including food security, income, macro- and micro-nutrient intake and dietary diversity. Mangrove ecosystems offer a wide range of services for the people that live nearby, including fisheries – and fish nurseries – that provide key sources of protein and micronutrients, as well as a critical income opportunity for many community members.

Residents also use the mangrove forests for timber, fuelwood, medicinal purposes, crafts, and more.

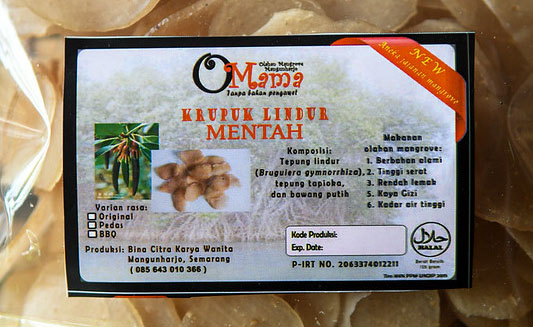

The leaves and fruit of the mangrove trees can be eaten, too, and some community members dry and grind it into flour, which can then be made into a range of processed products.

For each of the three research sites, the researchers are undertaking a coastal vulnerability assessment, which examines three dimensions: exposure to stresses, associated sensitivity, and adaptive capacity. The assessment takes into account a wide range of variables, including geomorphology, shoreline change, the coastal slope, the tidal range, mean sea level, wave height, stakeholder engagement and community awareness.

They also carry out socio-economic surveys, which assess the contribution of mangroves to the livelihoods, food security and nutrition of the local communities. This includes consideration on the gender dynamics of these issues, which can vary from place to place: for instance, in Banyuwangi, women usually collect shellfish (such as oysters and clams), while in Demak, fishing is mostly done by men, and women are generally involved in post-catch activities such as sorting, selling, and processing. In both areas, mothers are usually responsible for managing food budgets and deciding what foods are to be bought.

Possibly, the surface level change in Timbulsloko is happening due to the rising sea level, but another possibility is land subsidence

Residents also use the mangrove forests for timber, fuelwood, medicinal purposes, crafts, and more.

Lindur flour, which is processed from the fruit of the Bruguera gymnorhiza mangrove tree. CIFOR-ICRAF/Aulia Erlangga

Crackers made from lindur flour. CIFOR-ICRAF/Aulia Erlangga

The leaves and fruit of the mangrove trees can be eaten, too, and some community members dry and grind it into flour, which can then be made into a range of processed products.

Mufidah, a batik artisan, uses mangrove tree trunks as natural dyes for the batik she produces. CIFOR-ICRAF/Aulia Erlangga

Batik cloth with a mangrove tree pattern, complete with its roots. CIFOR-ICRAF/Aulia Erlangga

For each of the three research sites, the researchers are undertaking a coastal vulnerability assessment, which examines three dimensions: exposure to stresses, associated sensitivity, and adaptive capacity. The assessment takes into account a wide range of variables, including geomorphology, shoreline change, the coastal slope, the tidal range, mean sea level, wave height, stakeholder engagement and community awareness.

They also carry out socio-economic surveys, which assess the contribution of mangroves to the livelihoods, food security and nutrition of the local communities. This includes consideration on the gender dynamics of these issues, which can vary from place to place: for instance, in Banyuwangi, women usually collect shellfish (such as oysters and clams), while in Demak, fishing is mostly done by men, and women are generally involved in post-catch activities such as sorting, selling, and processing. In both areas, mothers are usually responsible for managing food budgets and deciding what foods are to be bought.

Women and children are typically the most nutritionally-vulnerable members of the family. So they are key interviewees for the nutrition element of the project. “The fish and other aquatic animals in the surrounding mangrove environment provide important nutrients needed especially by women of reproductive age and children. Mangroves provide nursery grounds and hiding places for these aquatic animals, but are rarely recognized for their role in contributing to food security and nutrition. Hence in this study we are collecting the data that will be used to highlight the role of mangroves in the livelihoods, food security and nutrition of the people whose lives depends on them” said Mulia Nurhasan, Ph.D., food and nutrition scientist at CIFOR.

For the livelihood component, the survey focuses on the family members who fish in the mangrove areas, assessing the values of this activity to the economy of the households. “In Banyuwangi, the local fishers have a saying ‘Akeh tanjange, keh picise’ which means, the more the mangroves, the more the money. The local fishers know the benefits of having healthy mangroves to their livelihood, and we want to learn this from them,” Nurhasan said.

Women and children are typically the most nutritionally-vulnerable members of the family.

As the project progresses, the researchers are drawing out deep connections between mangrove health and coastal vulnerability, and evaluating the restoration and mitigation potential for places like Demak. As yet, however, it is not clear whether Timbulsloko’s remaining residents will be able to hang on to their beloved homes in the years to come – or whether these house will soon be underwater remnants, Atlantis-like, on the ocean floor.

Story development : Monica Evans | Editing: Julie Mollins | Video production: Aris Sanjaya | Web design: Gusdiyanto | Publication coordination : Budhy Kristanty

We want you to share Forests News content, which is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). This means you are free to redistribute our material for non-commercial purposes. All we ask is that you give Forests News appropriate credit and link to the original Forests News content, indicate if changes were made, and distribute your contributions under the same Creative Commons license. You must notify Forests News if you repost, reprint or reuse our materials by contacting forestsnews@cifor-icraf.org.