LIMA, Peru—Madre de Dios, a region of Peru best known for its gold fever, is not the only place in the country where a piece of land can be classified as a mining concession and farmer’s field at the same time.

Millions of hectares of land in Peru are subject to overlapping claims, giving some indication of the complexity of land-use classification and titling in the country. Decentralization is one of the reasons for this; land-use powers and responsibilities have started to be distributed across government agencies and directorates that often have competing mandates and powers related to land use.

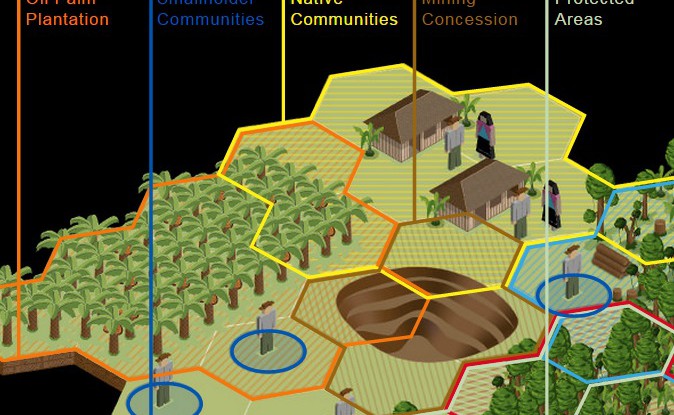

A case in point is Peru’s Ministry of Environment, researchers and legal experts say. While it is tasked with advancing REDD+ and other environmental conservation agendas, it doesn’t have many of the powers and responsibilities necessary to fulfill that mandate (see our interactive infographic to explore this for yourself).

“Most key powers related to land-use classification, planning, titling, and permitting are housed in other ministries. This makes it challenging for the Ministry of Environment on its own to change business as usual and move the country towards lower-emissions development,” said Ashwin Ravikumar from the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), author of a forthcoming report on decentralization and land-use policy in Peru.

While Peru has shown enthusiasm and increased political will to address environmental and forestry issues in recent years, it also faces challenges of balancing priorities of economic growth, poverty reduction and sustainable land use.

The national government’s priorities have become clear in recent months, with the Ministry of Finance’s approved economic stimulus package or paquetazo (endorsed by Peru’s President Ollanta Humala) aiming to set the country clearly on a path of 5 percent economic growth per annum in the wake of an economic slowdown associated with lower mineral prices. The package also waters down the Ministry of Environment’s ability to enforce territorial planning for economically optimized and holistically designed land-use activities.

Institutions have been set up to improve coordination and resolve overlapping or conflicting power disputes between national, regional and local governments and across sectors but have had limited success, according to Pablo Peña from the Peruvian Society for Environmental Law (SPDA).

“Some were set up with an initial excitement that has slowly faded away … they still formally exist but haven’t convened in years,” he said.

Peru will host the UN climate change negotiations in December, where the first draft of a post-2020 climate agreement is likely to emerge. Following intense discussion at a UN climate body meeting in June about how greenhouse gas emissions from land sectors can be addressed, it’s likely these issues will be at the forefront of the Peru meeting.

Why does land use matter?

The growing demand for resources in Peru and globally has seen the government introduce a range of policies to encourage agricultural production (palm oil, soybean) for national and international markets. This is the biggest cause of deforestation in the country and subsequently has led to an increase in carbon emissions; 61 percent of Peru’s emissions come from forestry, agriculture and land-use change.

Development and sustainability have long been considered to have mutually exclusive objectives, such that growth in sectors such as forestry, agriculture, mining, fisheries and infrastructure will always compete.

But this is not necessarily true in all cases. Crops depend on sufficient water supply and in Peru, this is regulated by the forests of the Amazon. So if policies focus solely on increased productivity, this will have downstream effects on water supply that should be considered and managed.

The five stages of decentralization in Peru

- Preparing regulatory frameworks

- Installing new regional governments

- Each region developing their national plans

- Devolution of powers so regional and local governments can exercise their functions

- Transfer of healthcare and education functions to regional and local governments

Laura Kowler’s research shows that the conflict between development objectives and sustainable outcomes comes down to who has the power to make what decisions, what implications this has on the land use outcome and who is affected by this outcome.

“What we find is that not all relevant actors participate (i.e. local communities, regional governments etc) in decision-making around land use that will ultimately affect their livelihoods and ability of future generations to meet their own needs,” said Kowler, a consultant with CIFOR.

No matter what the legal structures look like, ultimately land-use decision making is a political negotiation. “And political negotiations ultimately come down to power,” Ravikumar said.

Who has power over land use in Peru?

Understanding the process of decentralization in Peru is key to unpacking the complex role of different agencies in land-use planning and governance.

Peru’s five-stage decentralization process started 10 years ago with the aims of redistributing state power, funds, administrative duties and increasing public participation and improve natural resource management among three levels of government – national, regional and local. It’s still considered to be in its early stages.

An interactive infographic illustrates the different responsibilities each level of government in Madre de Dios has over different land use types, including oil palm, timber and mining concessions, REDD+ projects and indigenous lands.

At the national level, the three key government bodies are the Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation (MINAGRI), which has been overseeing land affairs since 1943; the Ministry of Environment (MINAM) established in 2008 with the authority to “design, establish, and execute government policies concerning the environment” and the Ministry of Energy and Mines (MINEM).

These ministries play a role in classifying areas of land to be used for:

- Agriculture

- Native forest

- Protected areas

- Mining

- Forest concessions

- Oil palm

MINAGRI determines optimal land-use aptitude (capacidad de uso mayor del suelo) through the General Directorate of Environmental Agricultural Affairs and uses this information to grant titles. “Land that is classified as forests, for example, can’t be titled,” Ravikumar said.

Another planning and land classification system is territorial planning (ordenamiento territorial) carried out by MINAM. One key component is Ecological Economic Zoning (ZEE), which aims to help decision makers determine the suite of suitable land uses in certain areas by collecting and modeling physical, environmental, social, ecological and cultural data.

“A really simple example is, if the data show an area has large tracts of pristine forest, a long history of indigenous community areas and poor soils, then it may be best classified as a protected area. An area of land with good water supply and degraded forest might be best considered for agricultural purposes,” Ravikumar said.

Before the economic stimulus package, there was some debate and ambiguity as to the binding nature of the Ministry of Environment’s zoning and planning tools. National policies and legislation stipulated that land uses were to be assigned by subnational governments under the approval of the Ministry of Environment’s ordenamiento territorial planning system. Subnational governments were supposed to harmonize their ordenamiento territorial plans with other development and social plans.

However, some legal experts argue that these tools were not mandated by law and their application was referential.

“Legally, even in cases where a territorial plan decided that a certain zone shouldn’t be used for mining or agriculture, the Ministry of Environment and the ordenamiento territorial offices of the subnational government didn’t have the legal power to stop privatization or concessions being granted,” said a source who did not want to be named.

“The recent economic stimulus package has essentially confirmed that the Ministry of Environment’s ordenamiento territorial cannot have any legal power and that it can only be used as a guiding tool.”

Once land has been classified and titled, Peru’s 25 regional governments are responsible for development plans; working with other regions to promote economic, social and environmental development; preserving and managing protected areas; and promoting sustainable use of forest resources. The power to regulate forest concessions for timber and non-timber forest products has been recently transferred to several regional governments.

Local municipalities have relatively few powers related to land use, with granting titles and issuing permits largely removed from their purview. They are able to provide agricultural extension services, regulate small, artisanal and informal mining and give binding opinion for mining concessions in areas of urban expansion.

This slow transfer of powers from national to regional and local level has had a major impact on the ability of those regions to effectively govern land.

|

Region |

Regional environmental authority established |

|

San Martin |

Dec 2010 |

|

Ucayali |

Feb 2013 |

|

Amazonas |

June 2013 |

|

Madre de Dios |

Feb 2014 |

|

Loreto |

In process* |

|

Arequipa |

unknown |

|

Piura |

unknown |

|

La Libertad |

unknown |

|

Cuzco |

unknown |

|

Junin |

unknown |

|

Cajamarca |

No** |

| * Has been slow | |

| **Apparently rather advanced in environmental issues |

|

According to the Ombudsman’s Office Report No 141 (2009) and the National Congress’ 2012/13 annual report, the transfer of powers was initiated before regional governments were fully formed and capacity fully built, with funds often assigned without a determined purpose.

Institutions have been set up to improve coordination between national, regional and local governments (intergovernmental coordination council) and across sectors (intergovernmental commission). The constitutional court exists to resolve overlapping or conflicting power disputes. But these national coordination bodies are rarely called upon.

There was some hope that regional and municipal environmental councils (CARs or CAMs) would bring actors from multiple levels to coordinate land use and environmental issues.

In practice, said Peña, local governments rarely attend the regional coordination meetings.

“And if the local or regional governments don’t have a real say in those decisions, what weight can [coordinating entities] have? Because they are not governmental agencies nor [create] binding decisions many agencies in the government simply don’t consult with them,” he said.

It is possible, he adds, that “as decentralization progresses, regional and municipal environmental councils will reinvigorate.”

Taking an inter-sectorial perspective, many forest-related responsibilities compete between MINAGRI and MINAM. Take timber concessions — MINAGRI (through the National Forest and Wildlife Service (SERFOR)) and its regional directorates are in charge of all authorizing, administering, controlling and monitoring of these concessions.

One of the schemes set up by the Ministry of Environment is Programa Bosques, which provides regional governments with four years of funding to strengthen the ability of public servants to protect primary forests in their region, for example to create business plans for ecotourism activities. The same scheme pays native communities US$4 per hectare for conserving primary forest area over a commitment period of five years. Three regional governments (Amazonas, San Martin and Pasco) and 48 native communities are currently participating in the scheme.

But MINAM is also dominant in REDD+ policy making and planning at the national level, even though many REDD+ projects must ultimately be implemented on lands under the purview of MINAGRI or regional directorates of agriculture. To fully integrate, for example, sustainable timber harvesting in concessions as part of a REDD+ project would need substantial dialogue between the two ministries. In fact, the only land-use type that does not involve an agricultural government entity is the designation of protected areas, which are currently the domain of MINAM.

Even without legislation that defines and valorizes ecosystem services and creates a regulatory mechanism that could make payments for such ecosystem services feasible, there has been much enthusiasm for REDD+ and PES to change the status quo by creating incentives for sustainable land management practices.

“But for these schemes to achieve such objectives, the Ministry of Environment would need have the power to influence existing land use practices and incentives,” Ravikumar said.

“And the new stimulus package may further diminish its powers in those domains.”

Struggles over future land management remain

A few months ago, the future of low emissions development in Peru looked promising. MINAM announced its intent to present a new national climate change strategy at the upcoming UN climate meeting.

But with Peru’s congressional economy committee recently approving controversial policy reforms that strip MINAM of its powers — fast track licensing for concessionaires (maximum 45 days allowed for impact assessments), a reduction in environmental fines, and reduced budgets of environmental watchdogs by directing all fine revenue to the public treasury — low-emissions development seems to have shifted down the priority list.

According to Peña, this reform is not as bad as it could have been.

“The original proposals seemed to have been worse (and there was a containment work done by the Ministry of Environment). OEFA [the Ministry’s pollution watchdog] has other key tools it can use for deterrence, such as temporary closing down a polluting site.”

The political events of the past few months have made the Ministry of Environment’s COP20 goal — to bring international attention to environmental successes in Peru — rather more difficult. It remains to be seen whether the December meeting will be an opportunity for Peru to constructively discuss and debate land governance issues, or to retreat from its sustainability and climate commitments.

Michelle Kovacevic is a science journalist and former editor of ForestsClimateChange.org. Connect with her on Twitter @kovamic

We want you to share Forests News content, which is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). This means you are free to redistribute our material for non-commercial purposes. All we ask is that you give Forests News appropriate credit and link to the original Forests News content, indicate if changes were made, and distribute your contributions under the same Creative Commons license. You must notify Forests News if you repost, reprint or reuse our materials by contacting forestsnews@cifor-icraf.org.