Nature-based solutions are increasingly part of the international dialogue on climate change. In 2019, funders agreed to pay Brazil and Indonesia for verified avoided deforestation. And the International Civil Aviation Organization is considering whether airlines will be able to use forest-based credits to offset their carbon emissions.

At the same time, new research has revealed that the climate impact of losing intact forests is six times worse than previously thought – and recent estimates suggest that stopping deforestation, along with other natural climate solutions, could provide 37 percent of the emissions reduction needed by 2030 to keep global warming below 2 degrees Celsius.

Forests are now firmly on the international climate agenda, said Frances Seymour, a distinguished senior fellow at the World Resources Institute (WRI). “Yet people think that REDD+ was something their grandparents did, that it’s over, and that it didn’t work,” she says, referring to the U.N.-backed approach to help fight climate change, known in its long form as Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation.

That is a misunderstanding, she says – and in a new peer-reviewed WRI Issue Brief, she and scientists from the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) and partner universities set out what’s been learned from REDD+ implementation on the ground over the past decade, and how future efforts can build on that experience.

“There is a very clear opportunity to integrate REDD+ with complementary global initiatives to protect and restore forests at jurisdictional scales,” said study lead author Amy Duchelle, senior scientist and leader of CIFOR’s climate change team.

The evolution of REDD+

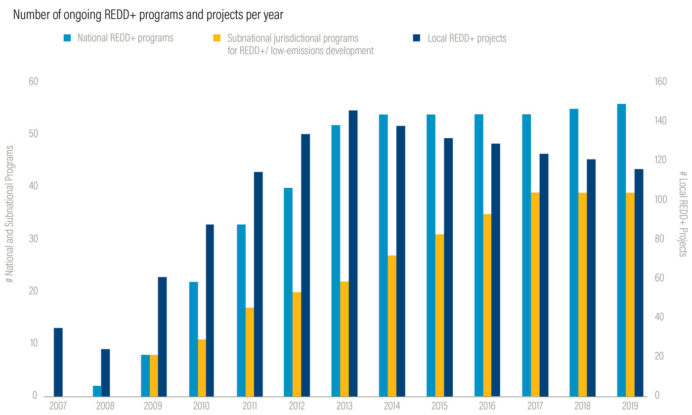

In the early years, most REDD+ activities took place in small, local projects while the scheme’s architecture was being debated by international climate negotiators.

But under the 2015 Paris Agreement, it was agreed that REDD+ accounting and finance would be implemented at the country level, or across sub-national jurisdictions like states and provinces. REDD+ is no longer a series of isolated, one-off projects.

Operating at the jurisdictional scale addresses the risks of leakage – displacing deforestation to other areas – and of permanence, Seymour said. “If you’re implementing at project scale, you can have one catastrophic fire that wipes out your whole inventory of carbon stock, but if you’re implementing it at a very large scale, even a pretty significant fire isn’t likely to wipe out the whole thing.”

Problems like insecure tenure or a lack of indigenous rights can also only be solved at the national level. “It’s no surprise, but the key barriers to protecting forests are barriers that can’t be surmounted at the level of a project.”

Yet REDD+ projects have been a useful testing-ground, and have offered some important lessons that will help to shape the future of REDD+, said Duchelle – even if that future has moved away from projects. One example is the Katingan project in the Indonesian province of Central Kalimantan, which is protecting an island of intact peat forest in a sea of oil palm and bolstering the livelihoods of communities in the project area.

“The key now is to figure out what the role of those REDD+ projects is in terms of overall carbon accounting: how Katingan fits in with what Central Kalimantan is doing, and what Indonesia’s reporting to the UNFCCC (U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change).”