LIMA, Peru—As a boy, Cándido Mezúa Salazar listened to Emberá elders tell stories that explained why the water in the river is cooler at some hours of the day than others, how to fish by day and by night, how to survive in the heat and the cold.

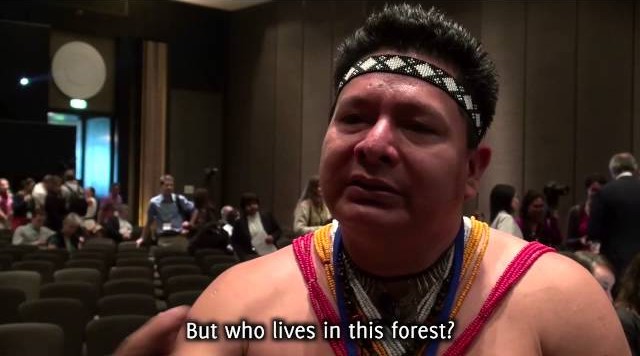

“These are things we learn from the landscape,” said Mezúa, who heads the National Coordinating Committee of Indigenous People of Panama, the representative body of the country’s seven indigenous territories. “We are part of the forest; you are part of the forest. Our Mother Earth is suffering, and the message you must take away is that everyone is responsible.”

His words during the opening plenary session on the second day of the 2014 Global Landscapes Forum in Lima, underscored the significant role of indigenous peoples in safeguarding forested landscapes and the importance of them having stronger tenure rights to their land.

The forum was organized by the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) and the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

The event on the sidelines of the annual UN climate change conference drew more than 1,700 people from 90 countries, including country climate negotiators, ministers, CEOs, indigenous leaders, civil society leaders and researchers.

The global agreements negotiated in Lima must “respect the rights of indigenous peoples and the most important thing in our lives, which is the land,” he said. “Without land, our rights would be doubly violated.”

TENURE AND CLIMATE CHANGE MITIGATION

Land rights were a recurring topic both at the Global Landscapes Forum and throughout the 12-day climate change summit, as indigenous leaders called for countries to grant titles to communities that are awaiting legal recognition.

In the Amazon basin, about 100 million hectares of indigenous communities’ land still have not been titled, according to Edwin Vásquez, who heads the Coordinating Committee of Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon Basin (COICA).

Where land rights are not clear, defending forests against outsiders is dangerous for indigenous people. Two leaders of the Asháninka village of Saweto, in Peru near the border with Brazil, were killed in September, along with two other men from the community.

Their widows, who were in Lima for the climate change summit, said illegal loggers had repeatedly threatened the leaders, who were trying to gain legal title for their community.

A six-country study by CIFOR has found that unclear land tenure is also a major obstacle to initiatives for reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD+). For REDD+ to work, it is crucial to know who has rights to the forest, who is responsible for emissions and who receives the benefits, according to the study.

Indigenous communities are been found to be particularly effective at keeping forest carbon sinks from becoming sources of greenhouse gas emissions. Research has shown that deforestation rates are lower in indigenous territories than on surrounding lands, including many officially protected areas.

When indigenous people lack title or their land rights are weak, their lands are vulnerable to deforestation. Having title, however, reduces deforestation and greenhouse gas emissions, according to a study by the World Resources Institute.

A study released during the climate summit found that Cacataibo communities in central Peru maintained 91 percent of their forest cover, compared to 66 percent in nearby communities.

These different studies draw on different methodologies to establish comparisons across landscapes and countries that require further analysis. However, results continuously raise questions and evidence around who is the best steward and who should own the forests, as these become central issues in the development debate.

But Vásquez warned against viewing forests only as carbon warehouses. Besides providing many other environmental services, forests and indigenous territories have a cultural and spiritual value, he said.

CHANGING VIEWS

Businesses are becoming more aware of indigenous people’s rights, Paul Polman, CEO of Unilever and chairman of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, said at the plenary session of the Global Landscapes Forum.

“We’re starting to work productively with forest communities and indigenous people,” Polman said. “For too long, their lives and livelihoods have been a hidden and unaccounted-for cost of the expansion of commodity production that has benefited the rest of us.”

He credited indigenous organizations such as COICA for helping to change that attitude.

We ask that governments understand our rights and our relationship with Mother Earth. That is all we ask

Mezúa said indigenous communities were willing to work with companies that respect their rights and act responsibly, but cautioned against reducing corporate social and environmental responsibility to charity handouts.

He also called for an indigenous territory climate fund, managed by indigenous people, to compensate them for safeguarding and protecting forests and enable them to pursue development on their own terms.

That was also one of the proposals presented at the climate change summit by the International Indigenous People’s Forum on Climate Change, which represents native peoples at the negotiations.

Respect for land, territory and resources is also part of that platform, as is respect for traditional knowledge and the role of indigenous people in adaptation and mitigation, and recognition of and support for indigenous people’s community-based monitoring and information systems for REDD+ projects.

“We’re not saying that we are the owners of all the forests in the world,” Mezúa said. “We have influence over them—they are part of our life. There must be clear rules that help safeguard those rights.”

Mezúa warned against investment schemes or development plans that focus on forests without respecting the “norms and principles” of the indigenous people who live there.

“You can’t look only at the trees, the forest, the resources, the environment or the climate,” he said. “You have to look at the landscape from within, the way we do.”

Indigenous people will continue to protect the forests, Mezúa said.

“But we cannot do it alone, without the support of governments and the business community,” he said. “We ask that governments understand our rights and our relationship with Mother Earth. That is all we ask.”

We want you to share Forests News content, which is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). This means you are free to redistribute our material for non-commercial purposes. All we ask is that you give Forests News appropriate credit and link to the original Forests News content, indicate if changes were made, and distribute your contributions under the same Creative Commons license. You must notify Forests News if you repost, reprint or reuse our materials by contacting forestsnews@cifor-icraf.org.