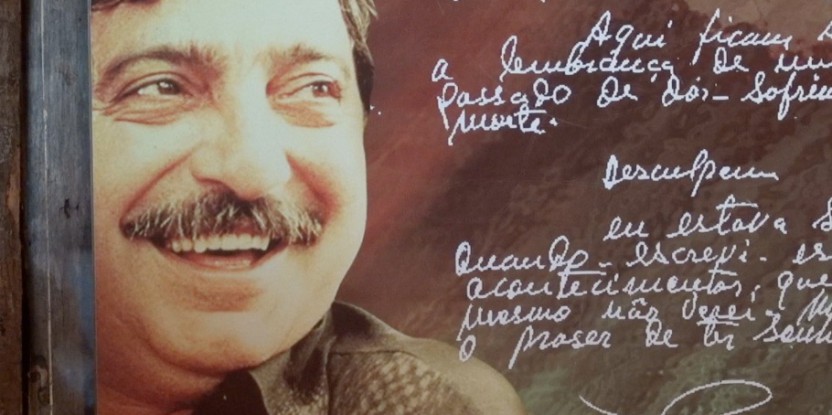

It’s impossible to talk about forests in Acre, Brazil, without mentioning the state’s home-grown hero: rubber-tapper, union-leader and Amazon-defender Chico Mendes.

His brutal murder 25 years ago made headlines around the world – and although the violence against activists in the Amazon hasn’t abated, Mendes’ death had a huge impact on the Amazon conservation movement, and galvanised his supporters to fight for a new kind of environmentally sustainable development in Acre.

Chico Mendes grew up in a poor family near the small Amazonian town of Xapuri in Acre in the 1940s. His parents, like many others, had moved to the forests of the western Amazon to harvest latex from native rubber trees for use in the allied war effort.

From the age of nine, Mendes began working as a rubber tapper for a large landholder. And although he never received any formal education, he eventually learnt to read, listened to foreign radio stations, and became keenly aware of the exploitation and injustices he and his fellow rubber tappers endured at the hands of the rubber barons.

During the 1970s, Brazil’s rubber tappers began to organise. Chico Mendes helped to set up a rural workers union in Xapuri and started to fight for rural rights.

By the 1980s, they had forged a powerful grassroots social movement, establishing a National Council of Rubber Tappers and assembling an alliance of rubber tappers, river dwellers, and indigenous people that became known as the “Peoples of the Forest,” to advocate for the rights of poor people and against deforestation.

In the 1970s and 80s, Brazil was in the grip of a military dictatorship that encouraged the clearing of the Amazon for cattle ranching. As part of this policy of expanding the agricultural frontier, rubber tappers were expelled from the rubber plantations by ranchers that wanted to clear the forest. The government offered to relocate these families to colonization projects elsewhere in the state – where many struggled with poverty, disease, and social dislocation.

If he were still alive, Chico Mendes would be happy – and still fighting for the Amazon, because this is a never-ending fight

Chico Mendes and his supporters fought back. Families peacefully occupied forest areas targeted by ranchers – a tactic known as empate. They stood in front of chainsaws and blocked bulldozers.

“At first I thought I was fighting to save the rubber trees; then I thought I was fighting to save the Amazon rainforest.

“Now I realise I am fighting for humanity,” Mendes famously said.

Now President of the National Council of Rubber Tappers, he partnered with the international conservation movement, and pioneered the idea of “extractive reserves” as a way for forest people to make a living while preserving the forest.

But this angered powerful landowners and their backers. In 1987, Mendes thwarted the plans of rancher Darly Alves Da Silva to deforest an area of forest that was slated as a nature reserve.

On December 22, 1988, Mendes was shot dead outside his home in Xapuri. Da Silva, his son and another man were convicted of the murder.

Marcos Afonso, a friend of Mendes, and now the Director of Acre’s Library of the Forest, says the ranchers made a huge mistake.

“They removed the leader to reduce resistance. On the contrary, it increased,” he said.

The murder sparked international outrage and massive protests around Brazil.

“Of course we were saddened by his murder and cried a lot – but the fight grew,” says Afonso.

“Chico’s legacy was his courage, his determination, and his belief in a different future for the Amazon.”

Ten years after his death, Mendes’ allies swept to power in Acre, setting up the self-proclaimed ‘Government of the Forest,’ and instituting a range of green, low-carbon development policies designed to safeguard the state’s remaining swathe of the Amazon.

“Our state is an international benchmark for how to intelligently use forest resources without destroying forests, ” Afonso says.

Mendes’ legacy is felt not just in Acre, but across Brazil. A year after his death the country’s first extractive reserve was established; now, there are at least 48, covering more than 12 million hectares of the Amazon. CIFOR research on some of these reserves has found that they have resulted in positive development and conservation outcomes.

“The rubber tapper movement that Chico Mendes led was a catalyst of profound change in Brazil,” says senior CIFOR scientist Peter Cronkleton.

“As a result, the forest peoples throughout Brazil gained the opportunity for recognition of their property rights over forest resources.”

“In fact, besides extractive reserves, these changes have led to a number of innovative property models like sustainable development reserves and agro-extractive settlements that allow rural people to maintain forest based livelihoods,” he said.

There are still many challenges in the Brazilian Amazon. According to a Brazilian NGO, nearly 1000 people have been murdered in rural land disputes across Brazil’s Amazon since 1985.

And although deforestation rates have dropped dramatically since Mendes’ time, the forest remains threatened, from fire, unsustainable logging, infrastructure development and agricultural expansion.

But Afonso believes Mendes would be proud of developments in Acre.

“I often talk to Chico’s children, and I ask them, ‘How would Chico Mendes feel about what we’re doing today?’ And they always answer, ‘He’d be very happy,” Afonso said.

“If he were still alive, Chico Mendes would be happy – and still fighting for the Amazon, because this is a never-ending fight. There are old, outdated forces in politics and the economy, which still have an anthropocentric view of development.”

“We need to continue resisting and developing new ideas and models,” he said.

“But I think we’re doing justice to Chico’s legacy.”

For more information on issues discussed in this article, please contact Peter Cronkleton at p.cronkleton@cgiar.org.

We want you to share Forests News content, which is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). This means you are free to redistribute our material for non-commercial purposes. All we ask is that you give Forests News appropriate credit and link to the original Forests News content, indicate if changes were made, and distribute your contributions under the same Creative Commons license. You must notify Forests News if you repost, reprint or reuse our materials by contacting forestsnews@cifor-icraf.org.