This is the first of seven stories highlighting the recent publication of a special issue of the International Forestry Review focused on CIFOR research.

Nonprofit organizations (NGOs), governments, and donors see multi-stakeholder forums (MSFs) as a transformative solution to the challenges of land and forest degradation. However, forum organizers need to do more than simply bring different stakeholders together to talk about a common challenge, according to a new research paper published in the International Forestry Review. More action is needed to support transformational change.

Researchers with the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) conducted interviews with the organizers of 13 MSFs in Brazil, Ethiopia, Indonesia and Peru, which were organized to address unsustainable land and resource use in subnational landscapes or jurisdictions.

Interviews focused on the organizers’ perceptions of how they thought their forums would achieve objectives, how power relations and other contextual factors may have impacted proposed pathways to change, and the role that MSFs would have played in such pathways.

Findings showed that most organizers believed if disempowered stakeholders were included in their MSFs – such as women, Indigenous Peoples and local communities – they were addressing historical inequalities in access to participation and decision making.

Yet they generally failed to include any specific measures to address inequalities. They also failed to develop clear strategies to engage with unsustainable local development and political priorities, according to the article.

“Achieving transformational change through participatory processes is not straightforward,” said Juan Pablo Sarmiento Barletti, CIFOR researcher and lead author on the study. “MSF organizers have to work at ensuring there is effective participation from actors that are normally underrepresented.”

Power inequalities

According to the authors, if marginalized groups are not heard, decisions are unlikely to reflect their priorities leading to outcomes that may not be in their best interests but that are still validated by their “participation.”

“There are different inequalities and contexts that prevent some people from participating in conversations or collaborations that could transform the way in which land is being used and thus support a way out of the climate emergency,” Sarmiento Barletti said. “Forum organizers need to be fully aware of these challenges to participation, design strategies to address them and be open to reflect on and adapt their approaches throughout the MSF’s process.”

Furthermore, the researchers saw no evidence of MSFs inspiring a real transformation in land and resource use in the cases they studied. “Many of the MSFs we studied served more as an informative or capacity-development platform than as a platform to pursue common goals,” said Nicole Heise Vigil, a researcher at CIFOR and coauthor of the study. Some of them were underfunded and most efforts led to outcomes without much visible impact.

“Extending participation to more stakeholders is a good idea, but most of the MSFs we studied did little to change the big picture,” Sarmiento Barletti added. “Some MSFs were—knowingly or not—driving towards a land-use scenario dominated by the agendas of the more powerful actors such as the private sector and the national and subnational governments. Most organizers did not believe that their MSF would be able to change how land and resources were used in the targeted landscape.”

Event or method

From the interviews, the researchers distilled two different but overlapping ways of understanding MSFs—as an event and as a method. Understanding these two forms, and when and why they occur, could explain why MSFs are still considered transformational platforms despite their limitations.

When people understand MSFs as events, they believe they can balance inequality between stakeholders by bringing them together periodically. This is where participants collaborate as equals towards common objectives.

But events do not always lead to tangible outcomes. “It’s a short-lived sort of moment,” Sarmiento Barletti said. “It’s an idealistic idea of ‘if we only talked more to each other everything would work out.’”

However, most organizers also saw MSFs as a method. This led to forums that brought actors together for implementation – and sometimes to co-design the implementation – of their organizers’ ideas.

To avoid conflicts, however, MSFs were designed – or shifted – to deal with the effects of land and resource use, rather than the structural issues driving the problems – they tended to address issues as “technical” problems, by raising awareness and developing capacities.

“MSFs as events and methods are not contradictory,” Sarmiento Barletti said. “They are two ways of understanding the same thing, but making the distinction helps to understand the different mindsets in the planning and design of MSFs and thus how to make them work better.”

Tools for change

The authors recommend two strategies to enable MSFs to support transformational change. First, organizers need to design procedures to address power inequalities between participants. Examples include using more equitable procedures, non-technical language in meetings, covering participants’ expenses, or offering training workshops to underrepresented groups to assure their effective participation. “Supporting empowerment and the organizational capacity of less powerful groups should be part of any strategy to address inequality,” said co-author Anne Larson, team leader, equal opportunities, gender, justice and tenure at CIFOR.

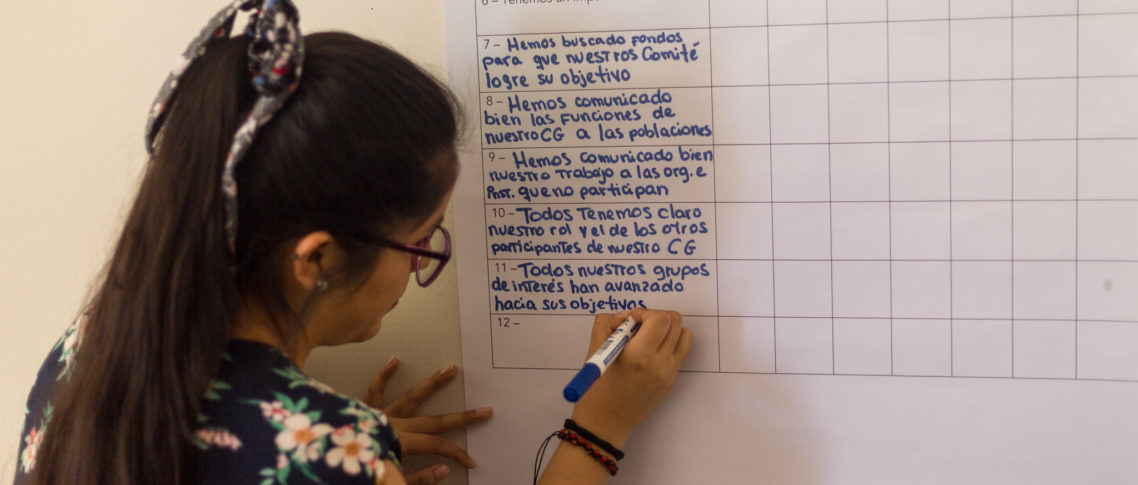

As part of the same research project, CIFOR researchers developed “How are we doing?”—a tool designed with MSF participants and organizers to reflect on the process, progress and priorities of their MSFs. This adaptive and reflexive learning tool, also available in Spanish and Indonesian language, allows MSFs to recognize and reflect on their challenges, supporting social learning to design strategies to achieve goal(s) equitably and effectively.

CIFOR researchers also developed which addresses issues of under-representation by providing tools designed to operationalize inclusion and address challenges in achieving equitable inclusion in MSFs. The guide focuses on women and Indigenous Peoples and provides insights that inform other under-represented groups.

Sarmiento Barletti stressed that MSFs must do more than just bring people together if they are to fulfil their transformational potential; they need to put in place clear strategies to address power inequalities among their participants to create solutions that support sustainable land and resource use.

The tools the scientists have developed for use with MSFs offer hope for better outcomes because they support better communication, mutual understanding and adaptive learning – especially as part of a strategy for change.

We’re learning to think more strategically about change, particularly about changing inequality – Anne Larson

The research supported by this work was undertaken as part of the CGIAR Research Programs on Policies, Institutions, and Markets (PIM) led by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), and Forests, Trees and Agroforestry (FTA) led by CIFOR. Both are supported by the CGIAR Fund Donors.

We want you to share Forests News content, which is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). This means you are free to redistribute our material for non-commercial purposes. All we ask is that you give Forests News appropriate credit and link to the original Forests News content, indicate if changes were made, and distribute your contributions under the same Creative Commons license. You must notify Forests News if you repost, reprint or reuse our materials by contacting forestsnews@cifor-icraf.org.