In Kenya’s Amboseli ecosystem, eight Maasai women risk their lives to protect their ancestral lands from poachers.

Together, these young women, aged 20 to 28, make up Team Lioness — one of Kenya’s first all-female community wildlife ranger units in the Olgulului Community Wildlife Rangers; they are the first line of defense for wildlife living on traditional Maasai land now known as the Olgulului/Ololarashi Group Ranch.

Team Lioness was formed in 2019 as a branch of the International Fund for Animal Welfare’s (IFAW) tenBoma security team. Since the COVID-19 outbreak, the women have devoted months at a time to patrols that take them away from their communities and put them in danger of wild animal attacks and encounters with armed poachers.

However, team member Eunice Maantei believes the risks of becoming a ranger are worth it to protect her native home from further destruction.

“I have lived around wildlife from a young age, and I have witnessed the destruction caused to our wildlife and environment at the hands of humans,” she said. “These events inspired me to be a change-maker, and when I was presented with the opportunity to become a wildlife ranger, I took it without hesitation.”

Chosen for their strong leadership skills, integrity and academic achievements, Team Lioness members like Maantei are among the first women from their families to secure paid employment. In patriarchal Maasai culture, women do not have many opportunities to support themselves, and most are dependent on their families to survive.

Despite these challenges, a Maasai woman’s traditional role in her community grants her valuable insider knowledge and a deep connection to the landscape, says IFAW.

These unique perspectives are vital for conservation efforts. Often, other women from the Maasai community feel more comfortable sharing information about potential poaching activity with female rangers who they know and trust, added team member Purity Amleset.

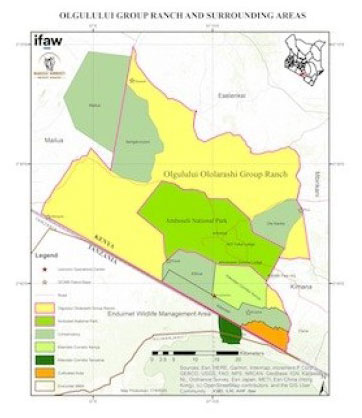

Map of Olugului/Olarashi Group Ranch conservation area.

In 2019, 38 elephants and four rhinos were poached in Kenya, according to Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) statistics, these numbers represent a drop from 2017, when 80 elephants and nine rhinos were poached.

Amboseli’s savannah ecosystem is famous for its elephants but is also home to countless other species such as lions and hyenas. Most at risk for poaching are small antelopes like dik-diks, gerenuks, impalas, Thompson’s gazelles, klipspringers and giraffes, according to Maantei.

When they encounter suspicious people, Team Lioness will attempt to detain them, calling KWS rangers for assistance. Earlier this year they detained a bushmeat poacher; last year they detained two other bushmeat poachers.

Team Lioness’s remarkable work opens doors for younger generations of Maasai women who want to protect their communities and pursue an independent livelihood.

Forests News is joined by Maantei, one of the eight rangers on Team Lioness, to talk about her work and the value of the Amboseli landscape.

Q: What inspired you to become a community wildlife ranger? Did being a woman make the decision harder for you?

I have lived around wildlife from a young age, and I have witnessed the destruction caused to our wildlife and environment at the hands of humans. These events inspired me to be a change-maker, and when I was presented with the opportunity to become a wildlife ranger, I took it without hesitation.

Women don’t get a lot of opportunities to have employment in the Maasai community, and most are entirely dependent on their families to survive. I want to be independent, and the best way to get out of this stigmatization was to become self-sufficient. Becoming a community wildlife ranger was therefore the easiest decision of my life.

Q: What is most rewarding about your job? What is most challenging?

Being able to support my family and seeing wildlife moving freely without risk of being poached is the most rewarding. The most challenging part is encountering dangerous animals and armed poachers while on patrols.

Q: Is there something you wish everyone knew about wildlife poaching in Kenya?

Poaching has decimated a lot of wildlife species around the world. In Kenya, tourism is the second highest source of foreign revenue in the country, but the dwindling number of wildlife caused by poaching activities will make the parks and reserves less attractive to visitors, meaning less income and loss of employment for a lot of people.

Q: What animals are most threatened by poachers in Amboseli national park?

Small antelopes like dik-diks, gerenuks, impalas, Thompson gazelles, klipspringers and giraffes.

Q: I know Team Lioness was quarantined in the field for several months earlier this year because of Covid-19. Are there other ways Covid has changed the way you work? Has poaching increased/decreased as a result?

The neighboring conservancies dependent on revenues suffered the most and lost approximately 50% of the workforce, we had to extend our patrols outside our area of operation to fill the missing gaps, translating to more hours in the field than normal.

A lot of people lost their jobs during the pandemic, which was the source of their livelihood. With fewer alternatives, some turned to poaching for subsistence and to survive. control by intensifying patrols in areas we identified as hotspots from the data collected over the years.

Q: What else can be done to prevent poaching in the national park?

Expanding the informer network helps us collect information about poaching activities before they happen. We also work closely with other government security agencies like Kenya Wildlife Service and the police to curb poaching activities.

Q: What does the national park and landscape mean to you personally?

They are our natural heritage set aside to preserve and conserve flora and fauna for future generations. They also protect the genetic diversity of plants and wildlife.

Q: Why — if at all — do trees/forests matter to your work as a wildlife ranger?

Trees mitigate climate change by absorbing carbon from the atmosphere and giving out oxygen which is essential to support life on earth. They are also home for many species of wildlife, bring rain to low lying areas, produce food for wildlife, provide natural medicines for many diseases and catch surface runoff water which prevents soil erosion. Without trees life on earth will be unbearable or cease to exist altogether.

We want you to share Forests News content, which is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). This means you are free to redistribute our material for non-commercial purposes. All we ask is that you give Forests News appropriate credit and link to the original Forests News content, indicate if changes were made, and distribute your contributions under the same Creative Commons license. You must notify Forests News if you repost, reprint or reuse our materials by contacting forestsnews@cifor-icraf.org.