“Climate change is one of the biggest threats we face as a society,” Nestlé CEO Mark Schneider said in September 2019. “We are running out of time to avoid the worst effects of global warming. That is why we are setting a bolder ambition to reach a net-zero future.”

Nestlé, Cargill and Mondelez, the world’s largest food companies, have all promised to help halt deforestation by 2030. Italian energy giant ENI, Rio Tinto, the world’s second-biggest miner, and other fossil fuel producers have pledged to slash their carbon footprints by 2050.

Significant promises, but what do they actually mean – especially when the planet would have breached the 2 degrees Celsius global warming threshold detailed in the U.N. Paris Agreement on climate change long before these promises actually bear fruit?

Unfortunately, we’re seeing little progress. Five years after the New York Declaration on Forests (NYDF), which aims to end forest loss with 200 pledges from companies, governments and non-governmental organizations, the results have been disappointing.

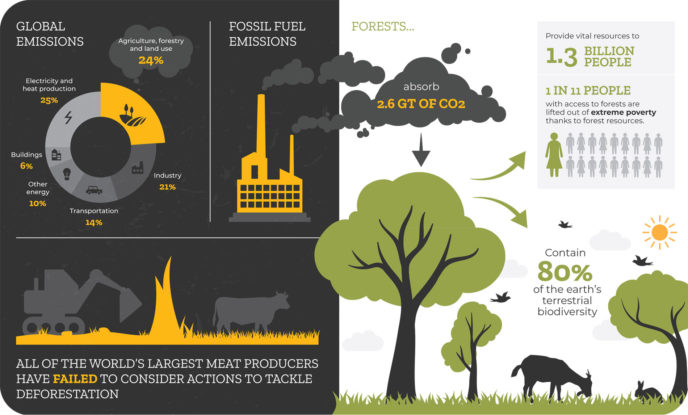

According to a recent report, all of the world’s largest meat producers have failed to consider actions to tackle deforestation – a failure that risks billions in investments, in addition to the longer-term impacts on forests and their invaluable role as carbon sinks.

“(T)here is little evidence that these goals are on track, and achieving the 2020 NYDF targets is likely impossible,” concluded a five-year assessment report on the declaration released in September 2019. It noted, bleakly, that where efforts had been made to stop forest loss, “these often lack ambition and remain isolated.”

If we are to take pledges of action seriously, and not merely applaud the promises, corporations and other entities must back up their words with detailed, transparent timelines, setting out what measures will be taken and when. Explain to us, as stakeholders in this planet and in our shared future, how pledges will be achieved, in painstaking detail. Then, we can properly assess the likelihood of these plans yielding fruit.

This might be loosely modeled on the sort of guidance and reporting routinely provided by publicly traded companies for financial markets and shareholders.

Certainly, no auditor or investor would accept vague assurances concerning corporate financials, but would demand detailed, long-range financial plans necessary to achieve stated goals. A similar approach to developing emission reduction plans, for example, would be useful for analysis.

Of course, detailed timetables aren’t always enough. ENI provided more detail than others on its emission-reduction plans – and analysts quickly noted the company’s plans to achieve zero carbon begin by boosting oil and gas production by 3.5 percent per year for five years.

The UNEP Production Gap Report, 2019 paints a very grim picture: the world is on track to produce far more coal, oil and gas than is consistent with limiting warming to 1.5 degrees C or 2 degrees C, creating a “production gap” that makes climate goals nearly impossible to achieve.

Nor is it only in primary resources that we find unverifiable pledges and vague timelines. Food giant Nestlé won kudos when it promised to cut greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to net zero by 2050. But we won’t see any details of its plans for two more years, it said in September 2019. How, then, can we evaluate what exactly that promise is worth?’

There is no doubt that corporations are seized with the environmental crisis. BlackRock’s chief executive Laurence Fink made that clear in early 2020 by announcing that the world’s largest asset manager would make environmental sustainability a core goal of its investment decisions.

Fink essentially put businesses on notice that they must all rethink their carbon footprints in view of the enormous risks posed by climate change. Such scrutiny should, in turn, spur corporations to look much harder at the details of their environmental commitments.

That reflects a trend in fossil fuel divestments, where global financial institutions and investment funds shift away from coal and coal-fired industries, in particular; and from fossil-fuel extraction more generally.

Sources: Responses to Weather and Climate: A Cross-Section Analysis of Rural Incomes. World Bank Background Paper. FAO (2014). State of the World’s Forests 2014; Noack, F.et.al (2015). Responses to Weather and Climate: A Cross-Section Analysis of Rural Incomes. World Bank Background Paper.

Some of that may be greenwashing but, as Fink has pointed out, it is also very good business to reduce risk. And climate change poses enormous risk.

It is essential that entities build much more rigorous monitoring and reporting mechanisms into their plans to meet environmental commitments. That should be accompanied by significant external mechanisms for monitoring and public reporting on results from corporate pledges. Governments and public leaders have a significant role to play in supporting the kind of enabling environment that will incentivize and encourage substantive action.

But we are nearly out of time and must act quickly. Already, the planet is about to exceed the 1.5 degrees C threshold after which we trigger catastrophe. The U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned in 2018 of the catastrophic consequences if we breach that threshold, and we are now on track for more than double that level by the turn of the century: 3.2 degrees C.

We must change course immediately and raise our climate action ambitions to an entirely new level. Forests, trees and agroforestry systems have a critical role to play in transforming many pledges into realities, offering multiple benefits beyond carbon dioxide sequestration (such as food, building materials, ecosystem services and biodiversity).

The world needs much more than a constant stream of good but vague intentions.

Now is the time for corporations and countries to step up and deliver what has been promised for decades.

Robert Nasi is Director General of the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR).

Satya S. Tripathi is UN Assistant Secretary-General and Head of the New York office at United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and Secretary of the UN Environment Management Group.

We want you to share Forests News content, which is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). This means you are free to redistribute our material for non-commercial purposes. All we ask is that you give Forests News appropriate credit and link to the original Forests News content, indicate if changes were made, and distribute your contributions under the same Creative Commons license. You must notify Forests News if you repost, reprint or reuse our materials by contacting forestsnews@cifor-icraf.org.