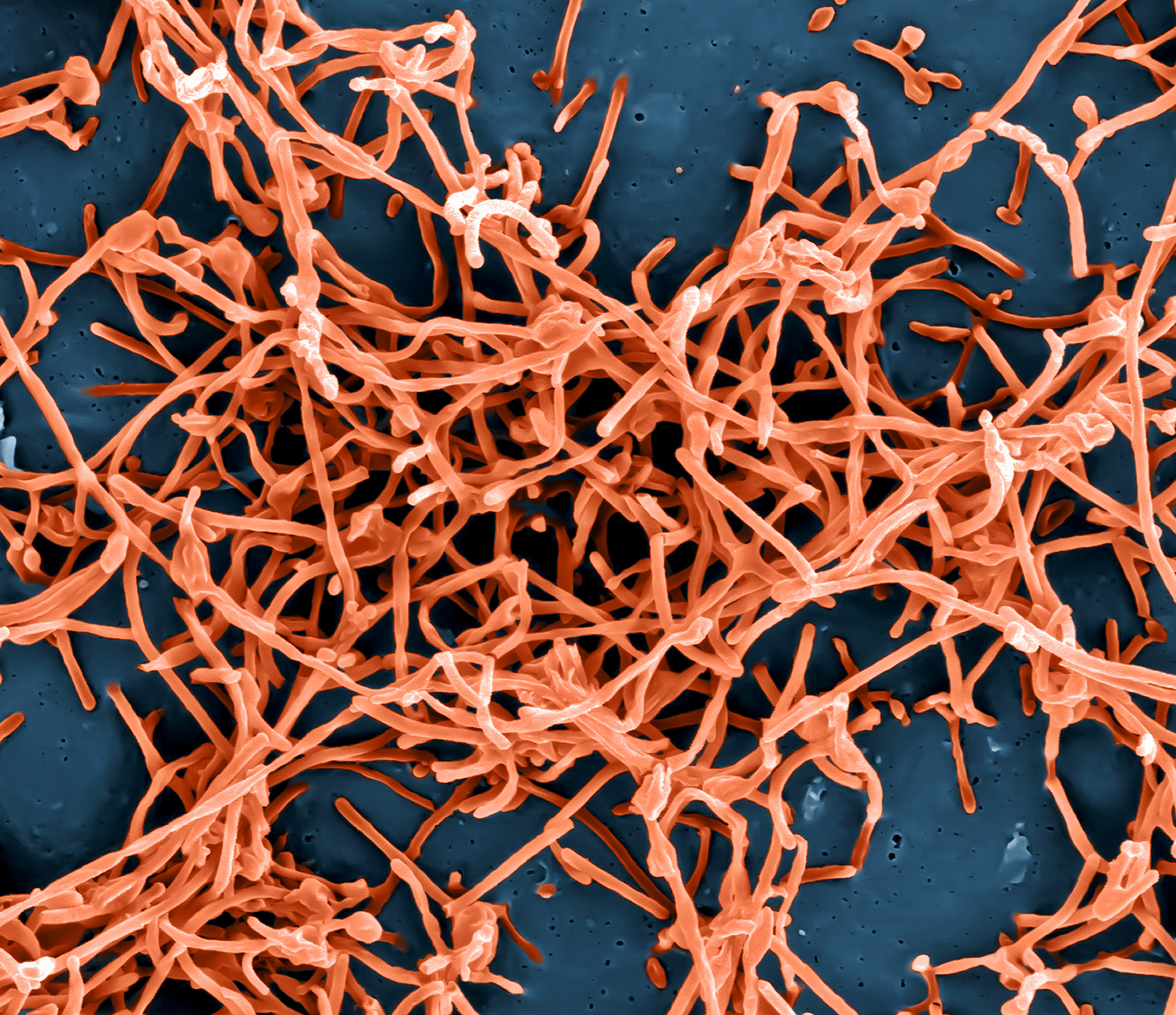

Ebola, the deadly hemorrhagic virus that can kill up to 90 percent of those it infects, has made a recent reappearance in the Democratic Republic of Congo. According to scientists, the area where the outbreak occurred – the remote Bikoro region in the northern Equateur Province – falls within areas deemed highly favorable for an outbreak of the disease.

The outbreak has already claimed 19 lives, including those of three healthcare workers, according to the World Health Organization. Since 1976, this is the DRC’s ninth Ebola outbreak, the highest tally of any single nation.

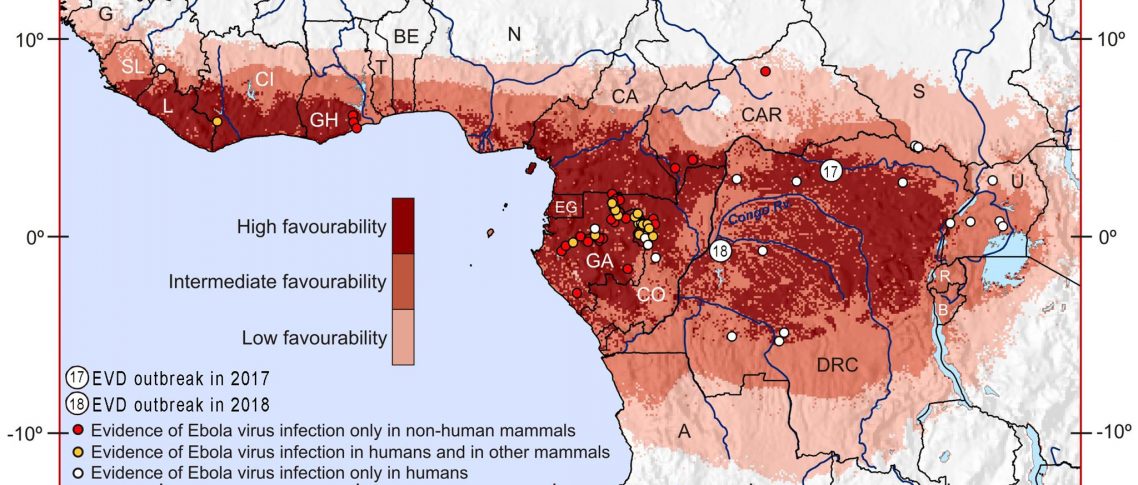

As part of a four-year study, scientists from the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) and Spain’s University of Malaga have been working on developing a biogeographical ‘observatory’ – a map that uses data on deforestation patterns and forest fragmentation, occurrence of potential virus-carrying species and climate to more accurately predict areas at high risk of Ebola outbreaks.

“The good news, though I don’t want to call it that, is that the area where Ebola is now appearing is right in the area we predicted is very favorable,” says John E. Fa, a CIFOR Senior Associate who has been leading the observatory’s project team alongside CIFOR Director General Robert Nasi.

“Our interest is to develop a more telescopic way of looking at problems – not just microscopic. We’ve got different strings of information that lead us to believe that we can be better at predicting where these outbreaks will take place.”

The observatory builds off Central and West African mapping projects the team has conducted on two of its three factors (species and deforestation).

“In the work that we’ve done, we’ve used a biogeographical analysis that allows us to look at the distribution of species linked to Ebola or presumed to be reservoirs of Ebola,” says Jesus Olivero from the University of Malaga. “We have about 21 species that may be linked.”

Reservoir species, he explains, are species that carry the disease but aren’t affected, such as the fruit bat, which is the most commonly presumed culprit for spreading the virus.

“There’s growing evidence that bats are the ones doing transmission. So we have looked at their distribution and can say that the distribution of fruit bats in Africa is very much linked to human presence. And that’s a major issue – the areas being disturbed by humans are much more appropriate as good habitats for bats, so possibility of contagion is higher.”

In the same way the virus is transmitted to humans, bats may also spread the disease to other mammals by, say, eating from a fruit that then drops to the forest floor and is later finished off by a primate. In light of the 2014 West Africa Ebola crisis, the Jane Goodall Institute reported that Ebola has caused the death of a third of the world’s gorillas and chimpanzees since the 1990s.

But, tagging the virus to certain animals is less important than zooming out to see the overall spread of carriers.

“The Equateur Province is very lush, with lots of mammal species, like bonobos,” says Fa. “But just because a particular species is found in an area where Ebola has struck doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s the species responsible for it. You don’t have to think about specific animals as transmitters. We decanted this using our favorability map.”

Deforestation not only brings people into closer contact with these species, but it also changes the viral equilibrium of forest landscapes and host species therein. This exaggerates ‘viral chatter’, or the way viruses seem to pop up suddenly among different species at different times.

Lastly, the scientists are using meteorological data to see how 21 different climate oscillations – recurring weather patterns such as El Niño – stack up against past outbreaks.

“We find that certainly one of them in particular – the Pacific oscillation – seems to be correlated with Ebola outbreaks,” says Olivero, caveating that the reasons for why are still being teased out. “We can postulate that if, for example, the virus requires drier conditions, an oscillation toward drier conditions could allow the virus to be much more active.”

Once the observatory is created, the researchers hope it will be taken into the hands of development organizations to avoid high-risk areas when planning forest conversion, and of public health organizations to serve as an early-warning system.

“I know it sounds very pastoral to talk about joint activities,” says Fa. “But we’re getting to the point of telling people where these places are likely to be. Then it’s up to a team of people to devise a plan to avoid those areas or support the public health departments to be able to confront the disease if it happens.”

We want you to share Forests News content, which is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). This means you are free to redistribute our material for non-commercial purposes. All we ask is that you give Forests News appropriate credit and link to the original Forests News content, indicate if changes were made, and distribute your contributions under the same Creative Commons license. You must notify Forests News if you repost, reprint or reuse our materials by contacting forestsnews@cifor-icraf.org.