A study conducted in the eastern Colombian Andes shows that farmers and recreational homeowners are willing to pay higher rates to protect a water supply and improve the quality of their drinking water.

The outcome of the findings from the study of the Chaina watershed may help stimulate programs that pay upstream landholders to protect land near the headwaters of a river that provides water to farms and towns downstream, said Sven Wunder, a principal scientist with the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR).

Recreational homeowners — generally wealthier — were willing to pay more than the local farmers, said Wunder, who co-authored a paper about the study, published recently in the journal Ecological Economics.

“One lesson from the study is that if you have a heterogeneous group of water users, you may possibly consider to charge them different rates,” Wunder said. “That could also be a way to increase revenues, and thus the amount of money one can pay for environmental services upstream.”

Environmental services include such benefits as water management and forest products, which people receive from natural ecosystems. Payments for environmental services (PES) are direct, conditional incentives to landowners for protecting natural resources on their land.

A program in the Chaina watershed pays upstream landowners to protect the stream, compensating them for income they would have received from expanding farming, ranching or logging. Almost 900 households began organizing a water users’ association in 2006 to improve their water supply by reducing sedimentation and increasing stream flow, especially during the dry season, Wunder said.

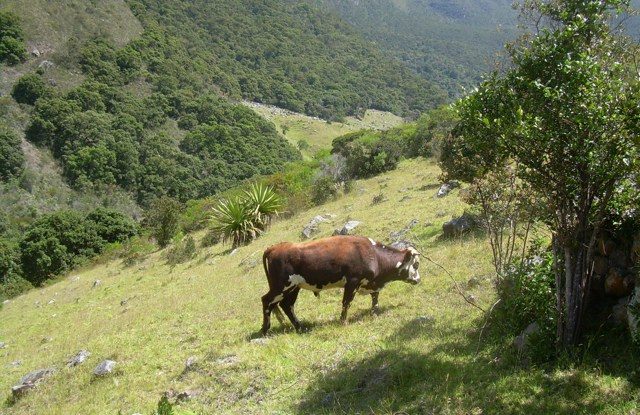

In an effort partly supported by CIFOR, water users negotiated with landholders near the Chaina’s headwaters, sometimes buying land outright and sometimes striking PES deals in which the landowners agreed to stop deforestation, stem erosion by decreasing cattle ranching on steep slopes, and allow soils and vegetation to regenerate along stream banks.

Water used to be clean and plentiful, but with a larger population and more economic activity, there’s less of it available, and sometimes people get angry

Under the program, each household downstream pays a monthly fee of 50 cents for water system maintenance. That amount includes payments to nine upstream landowners, which total $1,850 a year, according to the paper.

The program has helped preserve 162 hectares of natural forest, and led to the regeneration of 14 hectares of strategically located streamside vegetation, the researchers said. However, the current low fee is not enough to expand protection, which water managers say would make the program more efficient. Some water users are unwilling to pay more “because they are being asked to pay for something that they used to get for free,” he said.

“Water used to be clean and plentiful, but with a larger population and more economic activity, there’s less of it available, and sometimes people get angry,” he said. “Scarcity of an environmental service is something new, and people need to become mentally accustomed to the idea, before they might do something about it.”

Other water-management programs in the region are looking at ways to apply the Chaina study’s lessons to their own systems, Wunder said.

Although willingness to pay may differ depending on each situation, the Chaina research indicates that even in places where people have very different incomes and levels of water use, managers should not shy away from proposing a new rate structure, he said.

“The lesson is to look at what kind of users you have, maybe do questionnaires to find out what they are willing to pay. A proposal where the rates are differentiated may be controversial, but might also be a way forward to generate more conservation funding for watersheds,” Wunder said.

For more information about the topic of this research, contact Sven Wunder at s.wunder@cgiar.org.

This research forms part of the CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry (CRP-FTA).

We want you to share Forests News content, which is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). This means you are free to redistribute our material for non-commercial purposes. All we ask is that you give Forests News appropriate credit and link to the original Forests News content, indicate if changes were made, and distribute your contributions under the same Creative Commons license. You must notify Forests News if you repost, reprint or reuse our materials by contacting forestsnews@cifor-icraf.org.