Previously unrecognized, the Congo Basin’s Cuvette Centrale is now seen as an important carbon sink and the world’s largest undisturbed tropical peatland. Safeguarding this newfound treasure means actors on both sides of the border between the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and the Republic of the Congo (RoC) will need to work together to anticipate threats and govern proactively.

The Cuvette Centrale has always been known as a biodiversity hotspot. Its wetlands contain the first transnational Ramsar Site and are home to iconic species such as lowland gorillas and forest elephants. It also supports 11.1 million human inhabitants, most of whom rely on the rich natural resources for their livelihoods, according to a new brief from the Center for International Forestry Research and World Agroforestry (CIFOR-ICRAF).

However, it wasn’t until 2017 that a landmark study identified a significant amount of peat — a layer of partially decayed organic matter — in the wetlands. This discovery is heralded as one of “the key events of the decade for wetlands conservation,” according to the brief. Today, CIFOR-ICRAF is supporting its DRC colleagues in mapping the peatlands beyond the Cuvette Centrale. Their latest brief identifies key recommendations for governance cooperation between the two countries who share the peatland.

Encouragingly, the governments of DRC and RoC have an established history of working together on environmental issues, so there is reason to be optimistic about the peatlands’ ongoing function as a carbon sink, believes Denis Sonwa, a senior scientist at CIFOR:

“These two countries are already part of COMIFAC [Central African Forests Commission], CICOS [the International Commission for Congo-Oubangui-Sangha Basin] and cooperate on a range of biodiversity issues. I would say they have some common values and a common perception of forests,” he said. “Now that the importance of the Cuvette Centrale is clear, there’s an expectation that that type of cooperation will continue.”

Both countries signed the Brazzaville Declaration in 2018, which contains specific commitments to protect the Cuvette Centrale. They also participate in the Central African Forest Initiative (CAFI), which strives to implement the Paris Agreement, fight poverty and fulfil the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework. Under these agreements, the DRC and RoC each signed onto objectives — outlined in the brief — that can help sustainably govern the peatlands and foster its diverse communities.

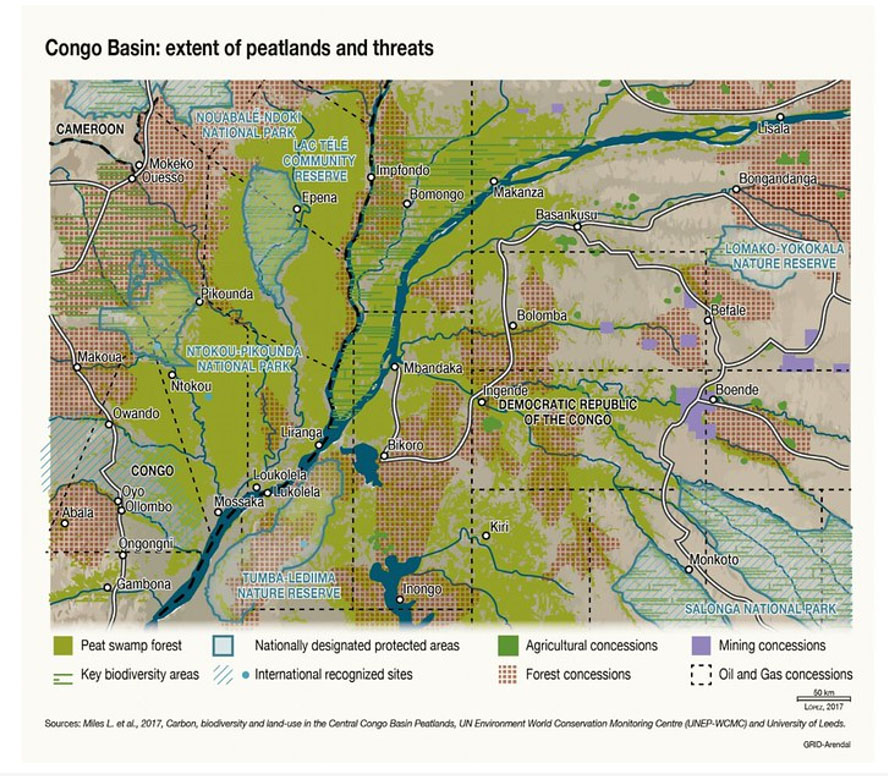

Nevertheless, the peatland is vulnerable to mining, deforestation, agricultural expansion and oil and gas concessions (see figure). Coordinating these different land uses poses an ongoing challenge for both local and national governments. Even the best intentions and signed commitments can be stalled by policy processing delays, notes the brief. When it comes to climate policy, there is also no universally accepted definition of a peatland, and it is up to the national government to decide how to integrate peatlands into their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs).

Extent of Congo Basin peatlands and threats. Nieves Lopez/Grid Arendal (https://www.grida.no/resources/12534)

Also, the lack of detailed landscape mapping across Central Africa means there could be more unrecognized peatlands outside of the Cuvette Centrale. Knowledge of additional peatlands could further improve natural resource management in DRC and RoC to reduce carbon emissions. This is an area where CIFOR-ICRAF’s scientific expertise could really support national policymakers in making wise climate and land-use decisions, said Sonwa. He and his colleagues are currently engaged in mapping other areas of the Congo Basin to identify peatlands.

Looking to the future, CIFOR-ICRAF scientists have identified several areas to improve governance cooperation and build capacity in the Cuvette Centrale. For example, both countries could implement a national system for peatland monitoring. Proactive monitoring could help governments move faster to protect peatlands that come under threat in the short term because information would be readily available to support decision making.

In the medium and long term, the DRC and RoC could streamline their national definitions of peat so that one country’s policy actions don’t threaten those of the other. They could also designate regional and local agencies to share the governance load and create a more responsive framework for peatland management.

There is still much research needed to understand how the newfound peatlands will interact with REDD+ processes (via CAFI). Researchers are also seeking to understand how the peatlands’ economic value could be realized through payments for ecosystem services (PES) or other forms of sustainable development.

“We are still in the mapping and analysing phase with these peatlands,” said Sonwa. “We need to understand how the peatlands can be ‘useful’ to the national agenda, ‘useful’ to the local populations and ‘useful’ in the global agenda while also being compatible with the sustainable management of this fragile ecosystem.”

The research discussed in this article was funded by the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD) through the Global Comparison Study on Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (GCS-REDD+) and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), especially through the Sustainable Wetlands Adaptation and Mitigation Program (SWAMP).

We want you to share Forests News content, which is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). This means you are free to redistribute our material for non-commercial purposes. All we ask is that you give Forests News appropriate credit and link to the original Forests News content, indicate if changes were made, and distribute your contributions under the same Creative Commons license. You must notify Forests News if you repost, reprint or reuse our materials by contacting forestsnews@cifor-icraf.org.