From Afghanistan to Cambodia, all throughout the lower Himalayas, extreme weather conditions are becoming the norm. A century ago, the hills were covered in forest. Now they are barren because of population growth, agricultural expansion and demand for firewood and timber.

Deforestation and landscape degradation mean that monsoons bring severe floods and the dry season brings drought, a challenge that curtails agricultural production, said soil expert Rattan Lal, who received the 2020 World Food Prize in a virtual ceremony broadcast from the Iowa State Capitol in Des Moines on Thursday.

“Of course there’s no water, because the previous water all washed away,” Lal said during a telephone interview with Forests News. “The solution is to reforest the hills back to what they were a hundred to 150 years ago — that requires commitment and cooperation among the countries where the watersheds are divided.”

Reforestation in the Himalayas will not stop drought-flood syndrome overnight, but it will stop in 25 to 30 years, in a generation. “It’s not a luxury, it’s required,” said Lal, who began innovating soil restoration techniques, which led to his influential “soil-centric” vision, in the 1990s at Ohio State University (OSU), where he currently serves as distinguished professor of soil science.

He advocates reforesting any land with more than a 5 to 7 percent slope to help with watershed management, climate change mitigation and adaptation.

DIGGING IN

Over five decades, and across four continents, Lal has honed his expertise in both policy matters and in soil science. The World Food Prize recognizes his work “developing and mainstreaming a soil-centric approach to increasing food production that restores and conserves natural resources and mitigates climate change.”

He is also lauded for the innovative conservation agriculture techniques he introduced, which have so far benefited the livelihoods of over 500 million smallholder farmers, improved the food and nutritional security of over 2 billion people and saved hundreds of millions of natural tropical ecosystems.

In a landmark research paper published in Science in 2004, Lal demonstrated that restoring degraded soils by increasing soil carbon and organic matter improves soil health, sequesters atmospheric carbon and offsets fossil fuel emissions.

He was recognized for his findings — which were adopted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change — when in 2007 the U.N. body was named a joint recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize with former U.S. Vice President Al Gore. Last Monday, Gore and Lal spoke at a virtual session titled “Translating Climate Science to Action” at the Borlaug Dialogue, a week-long conference held in conjunction with the World Food Prize each year.

“It’s an honor to be on the same program with Dr Rattan Lal,” Gore said. “He’s a longtime friend and a mentor to me.”

REMUNERATION FOR FARMERS

Lal says that farmers should receive payments for ecosystem services if they use techniques that sequester carbon in trees and soil.

“They should be compensated if we want them to adopt recommended practices – if we simply say do this for the good of the world and the good of humanity, it will never happen,” said Lal, who grew up on a smallholder farm in India learning first-hand about the drudgery of tilling soil with an oxen-drawn plow, and later advocated no-till agricultural practices.

Lal believes that the health of soil, plants, animals, people and ecosystems are inextricably intertwined. “When land is left to fend for itself, that’s when soil health and quality goes down,” he said. “Then soil cannot hold nutrients, it cannot hold water, it cannot denature pesticides and pollutants. They all end up either in water or air. If they end up in water it affects human health and if they end up in the air, it causes global warming and many other problems.”

GROUNDBREAKING STUDY

During his tenure at the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) in Nigeria during the 1970s and 1980s, Lal studied the impact of deforestation on climate change and hydrology, focusing on soil runoff and erosion in sub-Saharan Africa.

He monitored the effects of deforestation on climate and water balance. At that time, his work was not focused on climate change, but was concerned primarily with sustainable natural resource management — controlling runoff erosion and preventing land degradation. He not only demonstrated that deforestation should not occur, but recommended land restoration if it did.

In the mid-1980s, he received a visit from the late scientist Roger Revelle, a renowned early predictor of global warming. Revelle queried his observation that deforestation had changed climate and microclimate, and that the soil had degraded due to depletion of its organic matter because some had run off into the lake through erosion while some had absorbed into the atmosphere.

Revelle asked him if he could put it back, and that sparked ideas about restoration and specifically, Lal’s interest in whether carbon could be returned to soil from a climate change perspective.

“I am still trying to do that,” Lal said. “I don’t think the answer has yet been achieved, but that’s where the transformation happened — and reforestation is definitely an important component, but soil anywhere, all agricultural soils, especially in developing countries, are severely depleted because farmers take away everything — land is left to fend for itself and consequently carbon is continuously depleting, contributing to global warming.”

2020 World Food Prize laureate Rattan Lal (R) in works with a researcher. Credit: Kenneth D. Chamberlain, College of Food, Agricultural, and Environmental Sciences, Ohio State University.

Image is the property of the College of Food, Agricultural, and Environmental Sciences.

AGRICULTURAL SOLUTION

Alleviating agricultural expansion into forests involves investing in soil health so that production can be increased on existing farmlands. In sub-Saharan Africa, productivity on existing land could easily be doubled or tripled, Lal said.

“For most environmentalists, agriculture is a problem,” he said. “I think that is a little bit unfair because each one of us likes to eat food, and food comes from agriculture, so I think it’s our obligation to make agriculture a solution, rather than a problem.”

Land can become more productive by sequestering carbon through increasing soil organic matter content, which increases water capacity, nutrient cycling, fertilizer efficiency and full realization of the potential of germplasm — then agriculture becomes a solution.

Peatlands should not be drained and cleared for agriculture or forest plantations because they are carbon sinks — the moment we drain, they become a source of methane and nitrous oxide, Lal said.

“Clearing peatlands, draining them and then planting them with oil palm or rubber should be discouraged,” he added. “We have plenty of other lands, which can be used for that purpose — that is a very important policy point — policy-wise, developing any kind of plantations on peatland is a no-no — if peatlands are already cleared, the best solution is to restore them back to wetlands.”

AWARD ACCOLADES

In pre-pandemic times, the World Food Prize, which in the agricultural sector is considered on par with a Nobel prize, was presented each year amid much pomp and circumstance, capped off by a celebratory dinner.

This year, things were different.

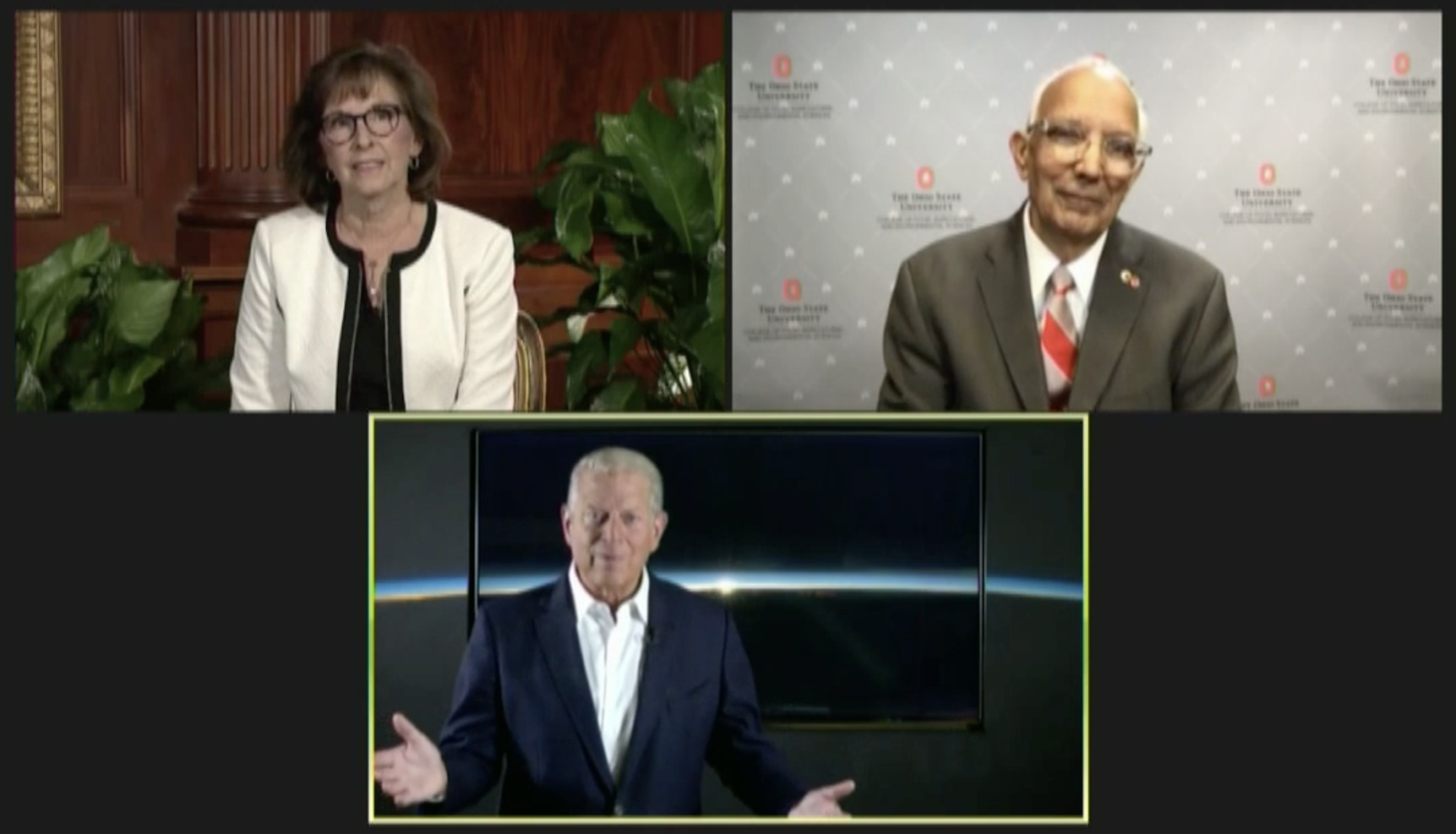

Lal was feted online by Barbara Stinson, president of the World Food Prize Foundation, and with a spectacular performance by Indian composer and musician A.R. Rahman, whose musical contributions to Slumdog Millionaire in 2009 earned him two Academy Awards.

“What I’m happy about is that they recognized soil,” Lal said, adding that he intends to invest his $250,000 award into an endowment fund he created at the OSU Carbon Management and Sequestration Center — newly anointed in his name by the university on Friday — to finance research and education. He has already contributed the $450,000 Japan Prize he won last year and other award winnings.

He hopes that others will contribute to the endowment, which is now valued at about $1 million.

“I’m looking for $5 million — that should be enough to have four or five grad students every year funded for that kind of research forever,” he said. “That’s my hope, that’s what I’m doing — and hopefully someone else is listening and they might say, hey, we will match you.”

We want you to share Forests News content, which is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). This means you are free to redistribute our material for non-commercial purposes. All we ask is that you give Forests News appropriate credit and link to the original Forests News content, indicate if changes were made, and distribute your contributions under the same Creative Commons license. You must notify Forests News if you repost, reprint or reuse our materials by contacting forestsnews@cifor-icraf.org.