This story was originally published by the Society for Ecological Restoration in SERNews

Across the globe, the degradation and destruction of millions of hectares of forest have contributed to depleted water supplies, soil erosion, food insecurity and loss of wildlife habitat. In response to this international crisis, over 50 countries have pledged to restore 350 million hectares of forests by 2030 in direct support of the Bonn Challenge.

Many initiatives are using a forest landscape restoration (FLR) approach, a process aimed at regaining ecological function and enhancing human wellbeing in degraded forest landscapes. FLR includes a suite of different land uses ranging from the protection of natural forests to the establishment of commercial tree plantations.

Crucial to the success of FLR is ensuring that the people who live in or near the areas to be restored have a role and a stake in the restoration initiatives. In fact, engaging stakeholders and supporting participatory governance is one of the core principles of FLR (Besseau et al. 2018).

Stakeholders can include local communities, indigenous groups, private landholders, businesses, non-governmental organizations and government entities, among others. There is also widespread need to build local capacity in the skills and ethos of trial-and-error that are central to adaptive management (Reed et al. 2016).

It is equally important to create “learning networks” that use workshops, meetings, and virtual communication to link the communities of practice – the people, groups, and interests that are connected to FLR efforts at the local, subnational, national, and global levels (van Oosten et al. 2014).

When it comes to stakeholder engagement and working with local people, restoration practitioners are often at a loss as to where to start. Collaborative monitoring, however, is an effective approach to meaningful stakeholder engagement.

Here we intentionally use the term “collaborative monitoring” rather than the more widely used “participatory monitoring” because collaborative monitoring recognizes the diversity of actors and interests – sometimes in disagreement – that share a forest landscape and are linked to restoration efforts, and it refers to the crucial importance of learning among those groups (Demeo et al. 2015; USDA Forest Service 2017).

On the ground, that means involving stakeholders at all stages of the FLR monitoring program, including in defining goals and objectives, the design of the monitoring approach, and the actual implementation of the monitoring activities in the field. Most importantly, stakeholders reflect upon and learn from the monitoring information together.

This cycle of learning through monitoring is repeated regularly. Benefits of collaborative monitoring include catalyzing learning and adaptation, building trust among stakeholders, gauging progress towards goals, and providing accountability.

Although some generic frameworks for planning and monitoring FLR are being developed internationally (e.g., IUCN; WRI 2014), many groups are independently developing national initiatives responding to global restoration targets without a transnational view on how to plan, implement, and monitor FLR (e.g., Meli et al. 2017).

The Atlantic Forest Restoration Pact in Brazil (Viani et al. 2017) and the U.S. Forest Service’s Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program (Demeo et al. 2015) have applied collaborative monitoring to measure success in large-scale restoration projects. However, FLR projects across regions or across the globe could learn from each other if cross-scale, multilevel, collaborative monitoring systems are put into place.

In 2008, we took the first step in what became a multi-stage project to aid practitioners in understanding the benefits and challenges of participatory monitoring in tropical forest management by synthesizing lessons-learned in that system.

In 2016, we saw that there was a need for greater understanding of the role of participatory monitoring in FLR around the globe, and we conducted a literature review to synthesize knowledge and experiences across multiple systems (see Evans et al. 2018).

In 2018, drawing upon those experiences, we took the next step: developing a tool to help FLR implementers assess whether conditions are in place for successful collaborative monitoring. We first identified the factors that contribute to successful collaborative monitoring in FLR by reviewing the literature; we then listed and synthesized these factors into a series of statements, initially totaling 106.

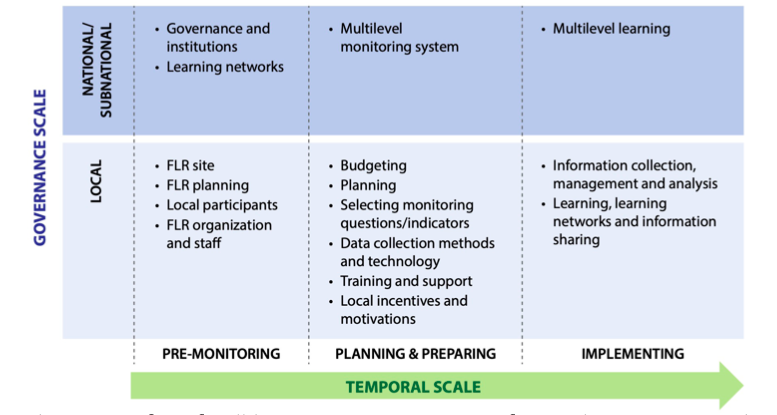

Twenty global experts then reviewed and ranked the success factors to identify which ones were the most important and useful according to a rubric. Important was defined as a factor that “can affect the outcome of the collaborative monitoring, is essential.” Useful was defined as “will help or contribute to carrying out collaborative monitoring, but may not be essential.” The result was a checklist of 42 core success factors to be assessed at local, subnational, and national levels in the planning and implementation of FLR.

Roadmap to success factors for collaborative monitoring in FLR. Success factors in the matrix are organized under the bulleted items.

Examples of success factors include those related to local implementing organizations and staff, for instance: “Collaborative monitoring is written into restoration staff work plans, so that monitoring continues even when there is a staffing change.”

Others have to do with data collection methods, such as: “The data collection tools and methods are geared towards quick and local processing and analysis without complicated calculations, and they provide for sharing with stakeholders at multiple levels and for application in future restoration efforts.”

Others describe local stakeholders’ relationships to the FLR project, for instance: “There are strong local intrinsic motivations to participate in the restoration, and local stakeholders perceive that there is a benefit to their participation.”

The complete list of success factors can be accessed in Evans and Guariguata (2019).

We designed this diagnostic tool to provide guidance on how to start collaborative monitoring, and we intend for the diagnostic to fill a gap in the global FLR effort to help implementers plan for collaborative monitoring and then strengthen their efforts over time through periodic assessments.

It can identify strengths and weaknesses in new initiatives, or pinpoint problems with ongoing implementation. It can also provide guidance on how to plan and prepare for FLR activities. Furthermore, the diagnostic explicitly addresses issues of scale, including multiple sites, governance levels, and changes over time.

The focus of our diagnostic on multi-scalar thinking (across jurisdictions, governance levels, and time) and its emphasis on learning (in the creation of learning networks and communities of practice, and scaling up the monitoring into systems for multi-scalar learning) is intended to reorient the focus from top down monitoring schemes focused on outputs and compliance towards learning and adaptation. We are now looking to collaborate with FLR sites that might want to “test-drive” the diagnostic.

We want you to share Forests News content, which is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). This means you are free to redistribute our material for non-commercial purposes. All we ask is that you give Forests News appropriate credit and link to the original Forests News content, indicate if changes were made, and distribute your contributions under the same Creative Commons license. You must notify Forests News if you repost, reprint or reuse our materials by contacting forestsnews@cifor-icraf.org.

Further reading

Besseau P, Graham S, Christophersen T, eds. (2018) Restoring forests and landscapes: the key to a sustainable future. Global Partnership on Forest and Landscape Restoration, Vienna, Austria

Demeo T et al. (2015) Tracking Progress: The Monitoring Process Used in Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Projects in the Pacific Northwest Region. University of Oregon, Eugene, USA

Evans K, Guariguata MR, Brancalion PHS (2018) Participatory monitoring to connect local and global priorities for forest restoration. Conservation Biology 32:525–534

Evans K, Guariguata MR (2019) A diagnostic for collaborative monitoring in forest landscape restoration. Occasional Paper no. 193. CIFOR, Bogor, Indonesia

IUCN, WRI (2014) A guide to the Restoration Opportunities Assessment Methodology (ROAM): assessing forest landscape restoration opportunities at the national or sub-national level. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland

Meli P et al. (2017) Four approaches to guide ecological restoration in Latin America. Restoration Ecology 25:156– 163

van Oosten C et al. (2014) Governing Forest Landscape Restoration: Cases from Indonesia. Forests 5:1143–1162

Reed J et al. (2016) Integrated landscape approaches to managing social and environmental issues in the tropics: learning from the past to guide the future. Global Change Biology 22:2540–2554

USDA Forest Service (2017) Expert Consultation on Monitoring Forest Landscape Restoration Workshop Report. United States Forest Service Office of International Programs, Washington D.C.

Viani RAG et al. (2017) Protocol for Monitoring Tropical Forest Restoration: Perspectives from the Atlantic Forest Restoration Pact in Brazil. Tropical Conservation Science 10: