I still remember the day, years ago, when the director general of the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) “invited” all staff to take part in a compulsory workshop about how theories of change work.

Squares, bubbles, arrows and other markings were drawn on pieces of paper and dotted throughout the room to juxtapose the familiar in a new context. Dull statements were marked on shiny stickers and placed on a cloth to demonstrate concepts related to inputs and impacts, as the workshop moderator fought against the waning concentration of skeptical scientists. Movement from left to right was the rhythmic focus of activities, while inputs to impacts served as a barometer of measurable change.

Years passed, and in 2018 I found myself in discussion with development specialists on a theory of change for the Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade (FLEGT) Action Plan, the European Union’s strategy to fight illegal logging and its negative impacts.

This time, the atmosphere, including the squares and bubbles, shiny stickers, left to right, was a complete contrast. The juxtapositions were more interesting. The moderator did not struggle to retain the concentration of participants.

In Yaoundé in 2019, together with an entire team of monitoring and evaluation specialists, I was trying to gauge the impacts of the Voluntary Partnership Agreement (VPA) in Cameroon. VPAs – trade agreements signed between the European Union and timber-producing countries as part of the FLEGT Action Plan – accompany a long list of projected impacts, on forests, people, the economy and more. But how can these impacts be measured?

That is when theories of change come in handy, when squares and bubbles, arrows and colors and dull sentences, in a sense, take on new meaning. I started dig into the FLEGT theory of change.

The reality is that the lives we are trying to have an impact on are not made of boxes and arrows. Multi-dimensionality is the rule outside our four walls.

Dialogues continued in other settings, including in Ghana and Indonesia which – together with Cameroon – were our initial target countries. Our fascination with the stories we heard about human experiences grew as we tried to bring them closer to our limited bi-dimensional theory of change.

After months spent interviewing hundreds of actors, the results are now published. The report is long, so allow me to delve into what I think are the most significant points.

A uniform methodology

The focus is on “uniformity,” not on methodology used, which has pros and cons. At the outset, the rumor was that there was so much literature about VPA impacts, actual visits to VPA countries were not needed. Rumors proved to be, well, rumors.

For FLEGT, an ambitious plan with operations in more than a dozen countries, measuring apples with apples is key.

For someone interested only in a logging area in Ghana, a community forest in Cameroon, a village in Indonesia, Vietnam or Guyana, a uniform approach may be immaterial, and results can still be useful to populate the theory of change. But when the question is whether FLEGT and the investments made in its name are having an impact on, for example, law enforcement and compliance in all VPA countries, then it is useful to have a uniform methodology.

We aimed to identify what contribution the FLEGT-VPA process has had on four key thematic areas, including: sustainable forest management and forest conditions; relations between, and development of, the formal and informal forest sector; jobs and employment; and law enforcement and compliance. Change was assessed based on the perception that 341 highly knowledgeable forest sector experts had between two points in time (before and after VPA implementation) and we built narratives about the VPA contribution to those changes.

The narratives (and the specific indicators collected) are very useful feedback loops to check whether the theory of change stands on its feet, and where the actions put in motion are working well, less well, or not well at all.

Different starting points, various changes

Obviously, both baseline and current values for many indicators differ among countries. The level of corruption, level of sanctions, or level of implementation of, say, forest management plans was different in Cameroon, Ghana and Indonesia before the VPA was ratified and remain different.

But this study is not a comparison of sampled country’s performance. Rather, it seeks to understand similarities and disparities of the contribution of FLEGT-VPA across contextually different countries.

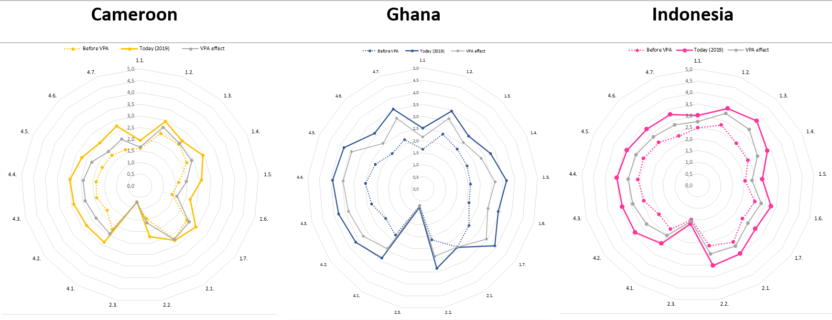

The information conveyed by the lines in each country is shown in the graph below:

For each of the 17 indicators for which change was measured, the chart shows perceptions before the VPA (dotted line), the situation today (full line) and the contribution of the VPA to change (grey lines).

If the grey line is very close to the dotted line, it means that the contribution of the VPA to the change (i.e. the distance between the dotted and full line) was very weak. Just imagine that sanctions in the forestry sector were not enforced before the VPA (value 0 in the graph), and that all issued sanctions today are enforced (value 5 in the graph). If the grey and the dotted lines are very close on the “sanctions” indicator, the VPA has not contributed much (or anything at all) to that change – at least not within the knowledge that more than a hundred experts can bring to the table.

Overall, the graph shows that change has occurred on many fronts and that the current situation appears more advanced in both Ghana and Indonesia than in Cameroon, with the VPA having generally had a positive contribution to the observed change.

A coherent set of actions, a few glitches, and many questions

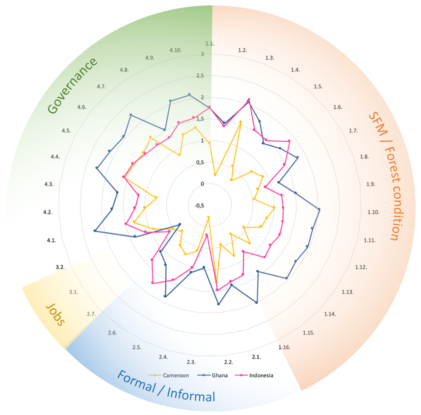

On a scale from strongly negative to strongly positive, we measured the VPA contribution to 35 VPA-targeted indicators. The graph below shows the 35 indicators – divided among the four thematic areas – and the VPA contribution to those indicators in the sampled countries.

If you see the glass half full, the graph shows at least two pieces of good news. First, almost all indicators have, on average, a positive contribution. Second, there is a remarkable degree of similarity among intervention areas in the countries, an indication that the FLEGT Action Plan, notwithstanding its complexity, has been able to set in motion a coherent set of activities supported by dozens of VPA implementers in various countries over the years.

If you see the glass half empty, the graph shows at least another set of news. First, several indicators in some countries are, on average, close to zero or just above it. Second, the contribution to positive impacts in one country seem to have not worked in another country.

Was the investment useless in those thematic areas and countries where the VPA seems to have been unable to climb away from a zero value? No, but – within the context of this study – it is the wrong question. Is it worth continuing investing in that area? Should resources be used to capitalize on the largest improvement areas, or redirect efforts to areas where least impact has been seen? How to maintain positive impacts if resources decrease? How to manage people’s expectations on potential impacts?

Answers are context-specific and there is no single “good” or “bad” answer to these questions. Yet results do inform possible answers which (again) need to be checked against the FLEGT theory of change, and possibly translated into new strategies for improved impacts.

To learn more, read the full article here.

We want you to share Forests News content, which is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). This means you are free to redistribute our material for non-commercial purposes. All we ask is that you give Forests News appropriate credit and link to the original Forests News content, indicate if changes were made, and distribute your contributions under the same Creative Commons license. You must notify Forests News if you repost, reprint or reuse our materials by contacting forestsnews@cifor-icraf.org.