The math is simple: about 25 percent of greenhouse gas emissions are connected with land use, and the traditional territories of indigenous peoples cover a quarter of the world’s land surface. Therefore, no climate solution is complete without respecting the rights of these ancestral environmental stewards.

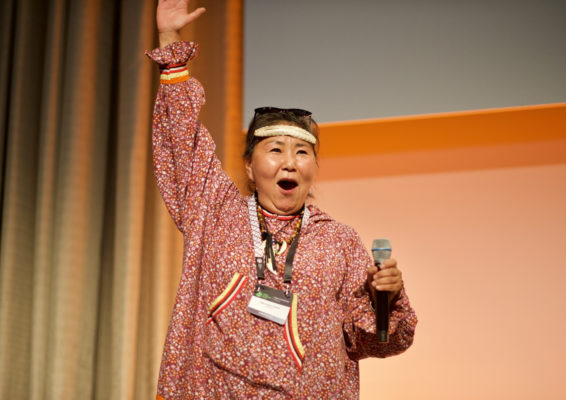

This is one of the main takeaways from the Global Landscapes Forum (GLF) in Bonn, Germany, which on 22-23 June brought together 600 participants from 83 countries to advance the recognition of rights as a centerpiece of the climate crisis discussion. The event, held alongside the UNFCC’s Climate Change Conference, also reached more than 7,500 online viewers and an additional 14 million through social media.

“When local communities have authority over their forests and land, and their rights are legally recognized, deforestation and forest degradation rates are often reduced,” said director general of the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR).

The reason is that tenure security gives local communities the possibility, and the incentive, to invest in resource management practices. “No rights, nothing goes forward,” summed up indigenous Amazonian leader Juan Carlos Jintiach.

David vs Goliath

Over two days, participants shared experiences from the frontline of indigenous people and women’s rights, often featuring a David-versus-Goliath scenario of local communities up against powerful corporations and corrupt institutions.

“There are many laws, but there is a lack of political will to implement them,” lamented secretary general of the National Coordination of Indigenous Peoples of Panama, Maximiliano Ferrer.

Ferrer’s experience echoed that of delegates from places as far flung as the Canadian Arctic, the Maasai steppe in Kenya and the rainforests of Papua New Guinea –all of them burdened with the stories of eviction, death and love for the land that the 350 million indigenous people in the world can tell in thousands of languages.