“Beautiful, isn’t he?” beams Age Kridalaksana, a young Indonesian ecologist in a research station nestled in the thickly forested hills of Gunung Halimun-Salak National Park, an expanse of mountainous tropical rainforest on the country’s main island of Java.

He gestures excitedly at his computer.

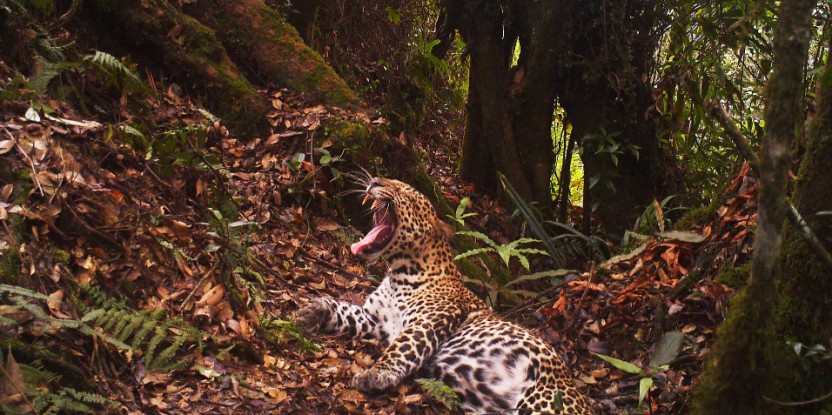

The photos are crisp, the colors striking; the spotted coat and silver-grey eyes instantly recognizable as one of the park’s most elusive mammals, the Javan Leopard (Panthera pardus melas), recently added to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s ‘Red List’ of world’s endangered species.

The big cats are usually extremely shy and enigmatic, but this healthy adult male, caught on a camera trap just two kilometers from the research station in Cikaniki, on the eastern side of the park, seems to revel in his newfound fame.

He stretches out, reveals his powerful canines with a huge yawn, then rolls over languidly.

It’s a display that seems to amuse Age.

“It’s as if he’s showing off, like he knows we are there,” he says, clicking through the images again.

At the foot of Mount Salak, known as ‘misty mountain’ to the local Javanese people, Gunung Halimun-Salak National Park covers 113,000 hectares and has some of the richest biodiversity in Indonesia

Yet, surprisingly, despite visits from scientists across the world, only a fraction of its 61 mammals species, 700 plants and 244 birds species have been extensively recorded.

The numbers of Javan leopard remaining in the wild are still unknown, with estimates ranging from 250 to 700.

That is why Age and colleagues from the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) and the Bogor Agricultural University (IPB) are here. With assistance from national park staff, they have been monitoring the size and range of leopard populations and their prey.

This is important, says Age, in part because it helps identify potential threats, like whether hunters or poachers are in the area, and if the big cats are moving closer to areas frequented by people.

“We need to understand how human influence is affecting the distribution of leopards and other species in this area,” he added.

The presence of large predators is also an indicator of the condition of the forests, a sign that the ecosystem is balanced.

But in Java, the forests are changing.

Java’s forests under threat

Home to half of Indonesia’s population and the epicenter of the country’s current economic boom, Java is losing more than 2,000 hectares of rainforest a year. Large-scale forest-clearing by mining and palm oil companies, as well as small-holder agriculture and tea plantations, is eating away at what little remains.

This includes forest in protected areas. According to an IBP report, between 1989 and 2004, Gunung Halimun-Salak National Park lost 25 percent of its forest from illegal logging and forest-clearing activities.

“If you lose the habitat, then you risk losing your top predators, which can have a devastating effect on the rest of the ecosystem,” said Age.

“Monitoring leopard populations now will help the park manage them and their habitat more effectively in the future.”

CIFOR reasercher, Age Kridalaksana and a national park officer discuss where to set up the camera trap. Mokhamad Edliadi/CIFOR

For example, national park staff could scale up efforts to protect locations identified as important breeding and feeding areas. Patrols to prevent illegal hunting and encroachment could be better targeted toward areas where humans and wildlife are more likely to come into contact.

But so far, the signs around the Cikaniki research station have been encouraging.

The 30 camera traps dotted throughout the park have captured over 1,000 images of barking deer (Muntiacus muntjak), common palm civet (Paradoxurus hermaphroditus), plantain squirrel (Callosciurus notatus), and malaysian field rat (Rattus tiomanicus)– an abundance of prey for a hungry leopard.

To the delight of the scientists, two other leopards – a relative of the Javan leopard with a black coat caused by a recessive gene mutation – also were captured on film.

“This is very impressive, considering that only a few hours away is the huge city of Jakarta, which encompasses 20 million people,” says Ken Sugimura, a Japanese scientist who leads the CIFOR project.

However, while leopard populations appear to be healthy, he says, national park staff should still be cautious.

CIFOR researcher Age Kridalaksana and a national park officer set up a camera trap in Gunung Halimun-Salak National Park. Mokhamad Edliadi/CIFOR

“A leopard’s home range can vary considerably, but is usually around 10 square kilometers. If their habitat continues to shrink, they could face increasing competition for food and shelter.”

“The risk then is that they will stray into communities that live in and around the park, targeting cattle and small dogs.”

Friend or foe? Leopard populations and the surrounding community

Although leopard sightings and incidents of conflict with the 300 communities around the park have been rare, villagers are fearful.

“We are worried the leopards may not only attack our livestock,” said Mr. Adwa, from Sentral, a village near to the research station. If hungry , he said, a leopard “may also attack human beings.”

While the camera trap photos revealed that leopards were travelling on paths used by villagers to collect wood, bamboo and other forest resources, Sugimura says the threat of conflict is still very low.

There is some overlap in habitats, he says, but so far contact is rare.

This could change, however, if leopards and people are forced into closer proximity.

“Deforestation and forest encroachment are the most significant threats we face,” said Iwan Ridwan, a forestry technician at the park.

As well as increasing patrols and enforcing anti-poaching laws and regulations, national park officials have also been collaborating with local communities to limit the impact of activities around the park.

“We continuously encourage them [the community] to manage the land sustainably, particularly in the areas that have been specifically designed for their use,” Ridwan said. “We also try to improve their economic condition, so that they will have some alternatives for their livelihood, reducing their dependency towards natural resources inside the national park.”

“So long as their [leopard] habitat is good, I think conflict between wild animals and the surrounding community will not exist.”

A paper based on findings from this project will be available in the coming months.

This project was led by Dones Rinaldi from Bogor Agricultural University, and Ken Sugimura, CIFOR, and with support from Gunung-Halimun Salak National Park. It was funded by the Japan Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute (FFPRI). This research is carried out as part of the CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry.

We want you to share Forests News content, which is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). This means you are free to redistribute our material for non-commercial purposes. All we ask is that you give Forests News appropriate credit and link to the original Forests News content, indicate if changes were made, and distribute your contributions under the same Creative Commons license. You must notify Forests News if you repost, reprint or reuse our materials by contacting forestsnews@cifor-icraf.org.